What’s your favourite seafood recipe? You’d be surprised at new and ingenuous ways found by designers and artists to utilize seafood waste to create innovative bio-based materials, cement and leather alternatives, as well as sophisticated artworks.

Sea Stone by Newtab-22

Aiming to help alleviate the issue of waste in the seafood industry, which results in seven million tonnes of seashells discarded every year polluting the land and water, innovation agency Newtab-22 based in London and Seoul has developed Sea Stone, a zero-waste project made from by-products of the seashell.

Sea Stone by Newtab-22

The concrete-like material is comprised by ground shells and natural, non-toxic and sustainable binders and features plastic hardness and aesthetic terrazzo-like texture. The process of making Sea Stone involves adding the mixture to a mould and leaving it to solidify into concrete-like pieces. This method is currently carried out manually to avoid the use of heat, electricity and chemical treatments, which means that each piece of Sea Stone unique.

Sea Stone by Newtab-22

Because seashells are rich in calcium carbonate, otherwise known as limestone, which is used to make cement, the two materials share similar properties. This makes Sea Stone a sustainable alternative to concrete in the design of small-scale products. The material has so far been used to make products such as decorative tiles, tabletops, plinths and vases.

Sea Stone by Newtab-22

The team deliberately do not want to use Sea Stone for large-scale or structural projects. This is because to truly replicate the strength of traditional concrete required in large-scale projects like buildings, an energy-intensive heating process would be required, which accounts for half of all the CO2 emissions that result from using concrete and would therefore lead to secondary pollution.

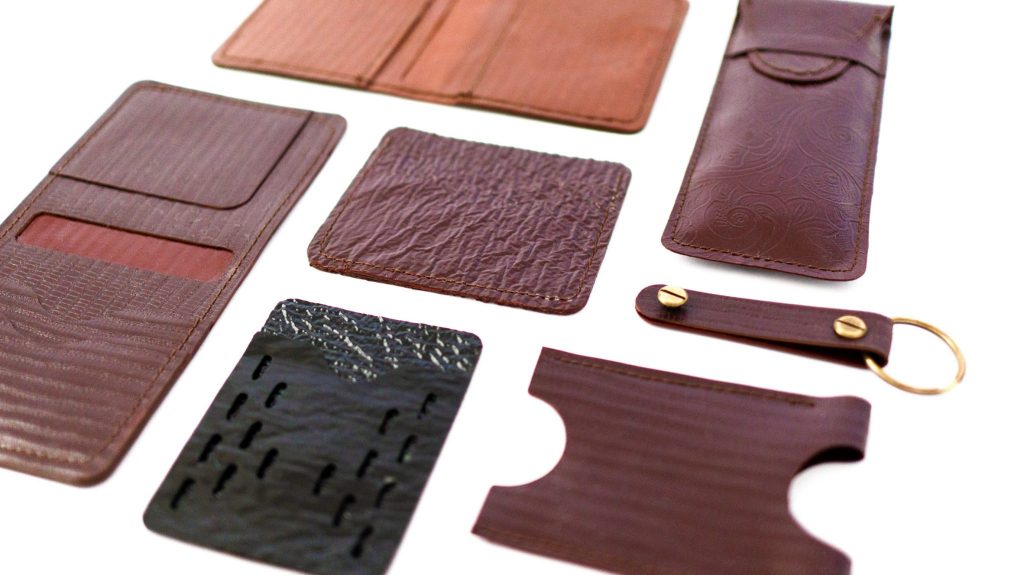

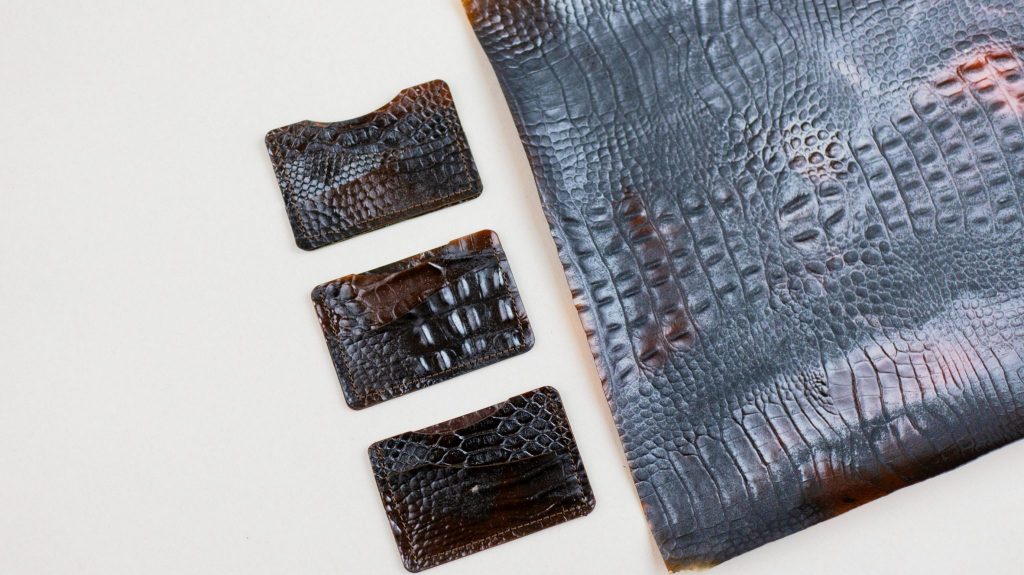

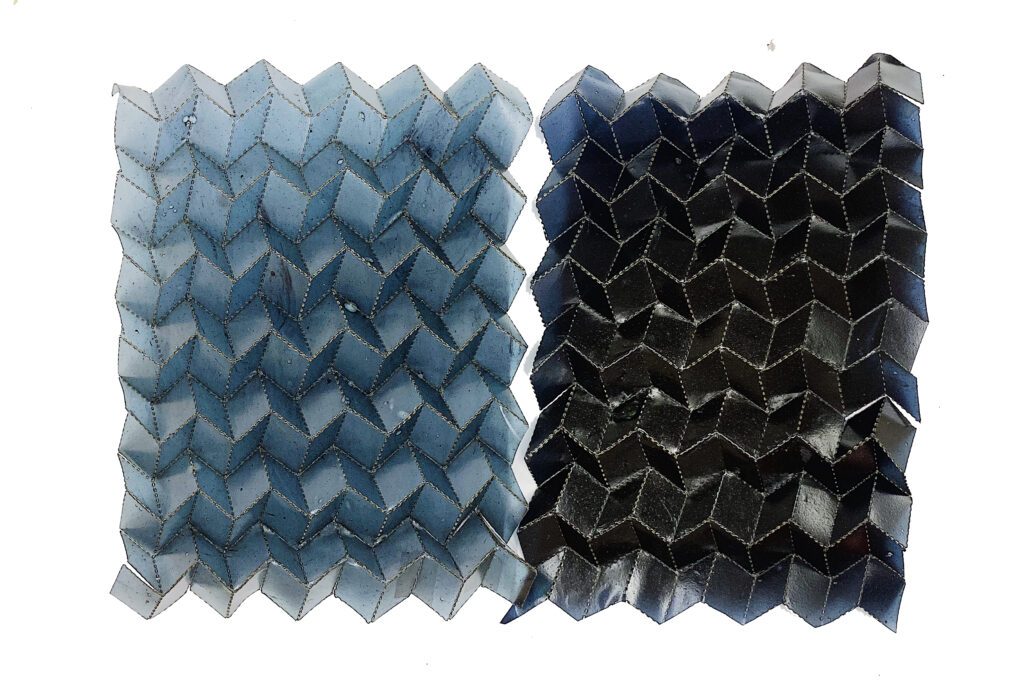

Tômtex by Uyen Tran

Vietnamese designer based in New York Uyen Tran has developed a flexible bio-material called Tômtex made from seafood waste shells. While the world is running out of raw materials, up to eight million tonnes of waste seafood shells and 18 million tonnes of waste coffee grounds are generated by the global food and drinks industry every year. The name Tôm, meaning shrimp, references the discarded seafood shells that are mixed with coffee grounds to create the textile.

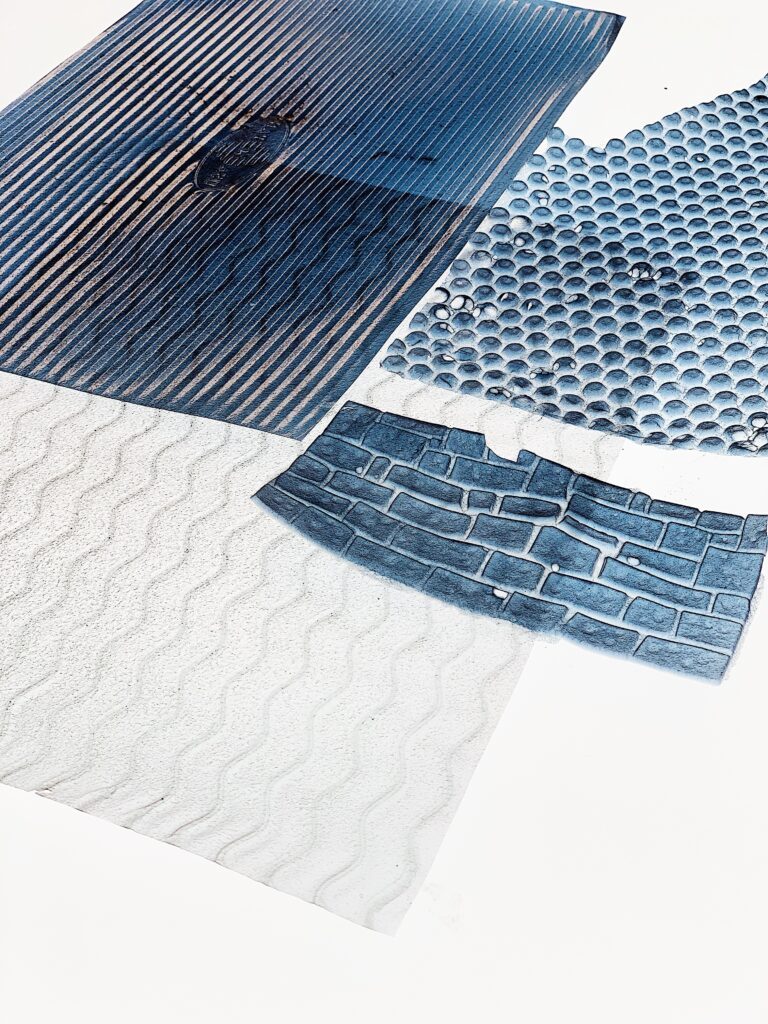

Tômtex by Uyen Tran

The material uses a biopolymer called chitin, which is extracted from waste shrimp, crab and lobster shells as well as fish scales. In combination with waste coffee from Tran’s own kitchen and from local cafes, this forms the basis of Tômtex. The mixture is dyed using natural pigments such as charcoal, coffee and extracts from food waste like onion skin adn beetroot juice and then poured into the mould where it is air-dried at room temperature for two days. The process doesn’t require heat, therefore it saves more energy and reduces carbon footprint

Tômtex by Uyen Tran

Using a 3D printing process enables the designer to create a variety of patterns, which are able to mimic the look of snakeskin or crocodile leather as well as more abstract embellishments, such as sequins. The biodegradable material is durable and water-resistant and at the same time soft enough to be hand-stitched or machine-sewn. Also, the material can be customised to be either leather-like, rubber/silicone-like or plastic-like by changing the recipe proportions and the way of making.

At the end of its life, the bio-material can be either recycled or be left to biodegrade.

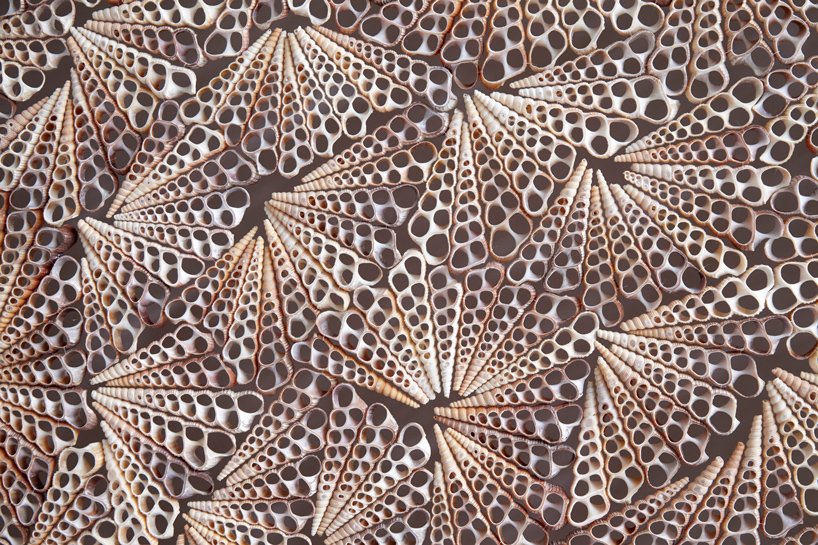

Seashell sculptures by Rowan Mersh (also header image)

Rowan Mersh, a multi-media sculptor who lives and works in London, uses windowpane oyster shell discs, dentalium shells, and turritella seashells to create intricate sculptural, wall-mounted installations.

Seashell sculptures by Rowan Mersh

Mersh’s pieces are inventive and multipurpose, bridging the realms of art, design and fashion. The artist slices the shells, grinds, shapes and polishes them by hand to reveal their lace-like central cavities. The shells are then bound together with fluorocarbon, as each shell informs the shape, size, and position of the next. The sculpture evolves like a web is spun, grown from central point, spiraling outwards to the sculpture’s boundaries.