Classic sculpture is a source of constant inspiration for contemporary artists. Exploring the timeless value of art and aesthetic practice, they reimagine well-known masterpieces to create a dialectic relationship between present and past, innovation and tradition, and illustrate our cultural heritage through contemporary languages.

New York based architect Daniel Arsham is known for his signature style, presenting a unique blend of antique and contemporary aesthetics. The sculptor has been granted access to molds and scans of iconic works of the collections of Europe’s major encyclopedic museums, such as Musée du Louvre in Paris and Acropolis museum in Athens.

Eroded sculptures by Daniel Arsham (also header image)

Investigating the temporal nature of artworks, Arsham has cast the original sculptures in hydrostone to produce perfect replicas of from Michelangelo’s Moses, the Vénus de Milo and other iconic masterpieces embedded into our collective memory.

Eroded sculptures by Daniel Arsham

Working at his artworks, the sculptor makes use of natural pigments, similar to those utilized by Renaissance sculptors, and then chisels individual erosions into the surface of the hydrostone, which also recalls the techniques used by classical masters. All this infers that the sculptures may have existed for a thousand years.

Eroded sculptures by Daniel Arsham

Finally, with his signature tactic of crystallization, the artist manages to question whether the works are decaying or actually growing towards completion, as crystals and minerals do.

Tattooed sculptures by Fabio Viale

In the works of Italian sculptor Fabio Viale, the vitality of real-life re-emerges from the stone surfaces, as a timeless past and current trends come together. He uses a refined and contemporary approach to historic sculpture-making. In an attempt to bridge the cultural gap between the West and the Middle East, the artist applies Japanese tattoos to the replicas of the famous works of art created by Renaissance sculptors.

Tattooed sculptures by Fabio Viale

In his latest work Amore e Psiche (Cupid and Psyche), which replicates the neoclassical masterpiece by Canova, he has disrupted its traditional interpretation through the tattooing of the female body with the wedding motifs of Middle Eastern brides. In such a way, he encourages reflection on the condition of women in the current geopolitical context on the themes of conquest, suffering and salvation.

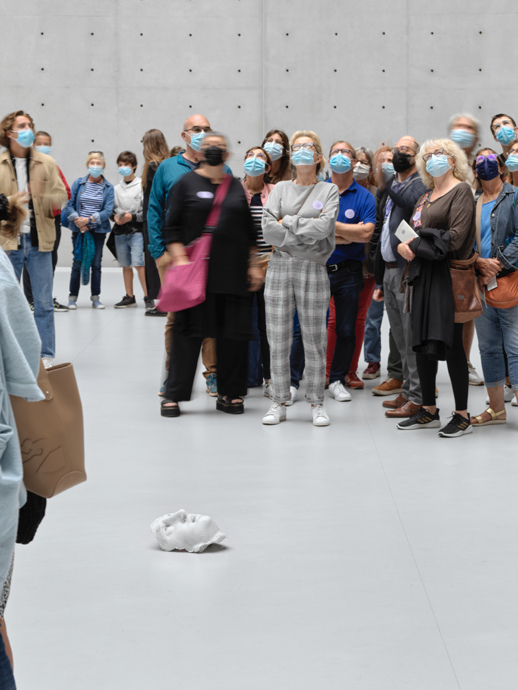

Wax sculptures by Urs Fischer

In one of his most popular works Untitled (originally shown back in 2011), Swiss artist Urs Fischer placed a life-size replica of Giambologna’s Abduction of the Sabine Women among wax sculptures, including an effigy of artist Rudolf Stingel, the sculptor’s friend and peer, and seven different chairs, ranging from an African stool to a banal plastic chair, all cast in wax. The large-scale candles were lit on the first day of the exhibition in the Parisian Bourse de Commerce and will continue burning until they melt into pools of wax by the end of this year.

Wax sculptures by Urs Fischer

The chairs were devised as symbols of contemporary globalization. While some of the chairs were modelled after the pieces from Mali, Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Ethiopia, from the collections of the Musée du Quai Branly to respond to the representations of inter-continental commerce and trade in the late 19th century; the airplane seats and garden chair evoke travel and the standardization of our contemporary world.

Wax sculptures by Urs Fischer

The artist describes the installation as a monument to impermanence, transformation, the passage of time, metamorphosis, and creative destruction. Within this context, as the candles burn, the sculpture becomes informal, even formless.