The use of light can lead to very diverse feelings. In religious symbolism, light is strongly connected to our ability to see: sacred texts use the theme of blindness to describe those who are spiritually lost, or risk taking the wrong path in life. In church architecture, light is considered a transformer of space, and it has always been tried to give a more spiritual aspect to the interior space and create a dreamy – or even mystic – atmosphere.

The Holy Redeemer Church by Menis Arquitectos

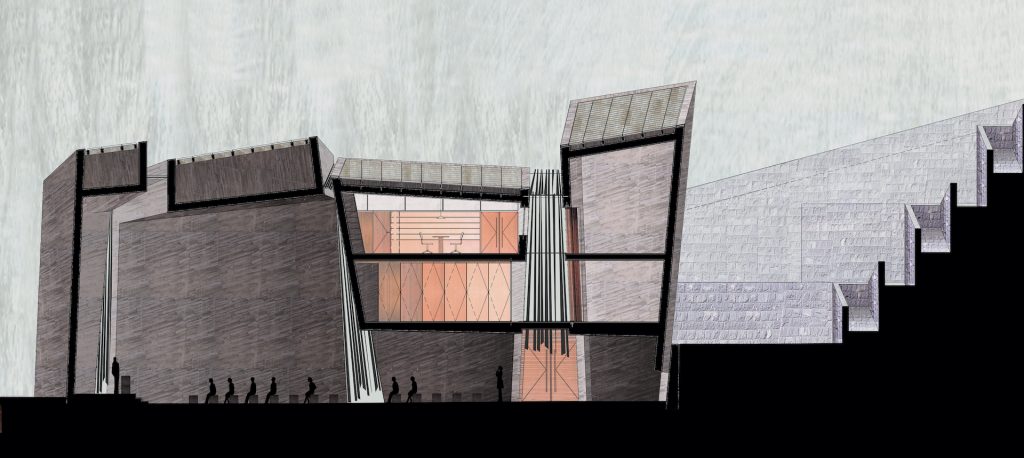

The Holy Redeemer Church on Tenerife island, Spain, by local studio Menis Arquitectos uses light in a subtle, mystic way. Built as part of a larger project in the Las Chumberas neighborhood that also includes a community center, and a square surrounded by greenery, all creating a welcoming public gathering place, the church takes shape as an uneven assemblage of large stone modules.

The Holy Redeemer Church by Menis Arquitectos

Inspired by the geology of the volcanic island, the volumes with their texture of the raw stone resemble naturally-occurring boulders, which makes them contrast the surrounding residential buildings.

The Holy Redeemer Church by Menis Arquitectos

The stone modules are meticulously positioned to optimize the penetration of the natural light throughout the day. Daylight enters the space through narrow crevices enclosed by metal and glass between the massive shapes forming the building.

The Holy Redeemer Church by Menis Arquitectos

At sunrise, sunlight forms a cross shape on the wall behind the altar turning the space into a symbolic cave. At noon, the altar, the confirmation, and the communion receive light through the skylight, while the confessional is lit by a shaft of light later in the evening.

Sola Church by Jaja Architects

Light plays with art in a new church in the town of Sola, Norway, recently completed by Copenhagen-based design practice Jaja Architects. Designed to be the new gathering space in the small town, the church is located at the end of the main street, its nave placed as its direct extension. Opposite the town hall, the two buildings form a new plaza with a continuous green park as a backdrop.

Sola Church by Jaja Architects

The nave is designed as a symmetrical space providing a calm and balanced experience. Behind the altar, a huge art piece by local artist Marie Buskov is installed, giving the church its own identity and a spiritual atmosphere. The opposite wall is defined by a composition of cuts and sloping wooden slats.

Sola Church by Jaja Architects

In combination with the stained glass the louvres filter and diffuse the daylight that penetrates the roof, lending the place a sacred and poetic touch. The sunlight lets the stripes of coloured light wander through the room, and after the sunset the space returns to its serene form.

Bahá’í Temple of South America by Hariri Pontarini Architects (also header image)

Developing the Bahá’í Temple of South America outside the metropolis of Santiago, Chile, Toronto-based Hariri Pontarini Architects has used light as the tool for spiritual and design inspiration. Drawing references from whirling dancers and Japanese bamboo baskets, the building features nine monumental glass veils framing an open and accessible worship space where up to 600 visitors can be accommodated.

Bahá’í Temple of South America by Hariri Pontarini Architects

An investigation into material qualities that embody light resulted in the development of two cladding materials: translucent marble from the Portuguese Estremoz quarries for the interior layer, and cast-glass panels for the exterior. Looking up to the central oculus at the apex of the dome, visitors will experience a mesmerizing transfer of light from the exterior of cast glass to an interior of translucent Portuguese marble. At sunset, the light captured within the dome shifts from white to silver to ochre and purple.

Bahá’í Temple of South America by Hariri Pontarini Architects

The final fabrication of the steel superstructure was made possible only through advanced fabrication techniques. The multitude of parts was assembled in Germany into manageable sections, and then shipped and assembled on site in Chile.