With sea levels set to rise, the underwater architecture has become a topic of discussion that architects eagerly address. For a long time, the innovations in architecture were limited to attempting new heights, but now several projects have tried to explore the depths of water.

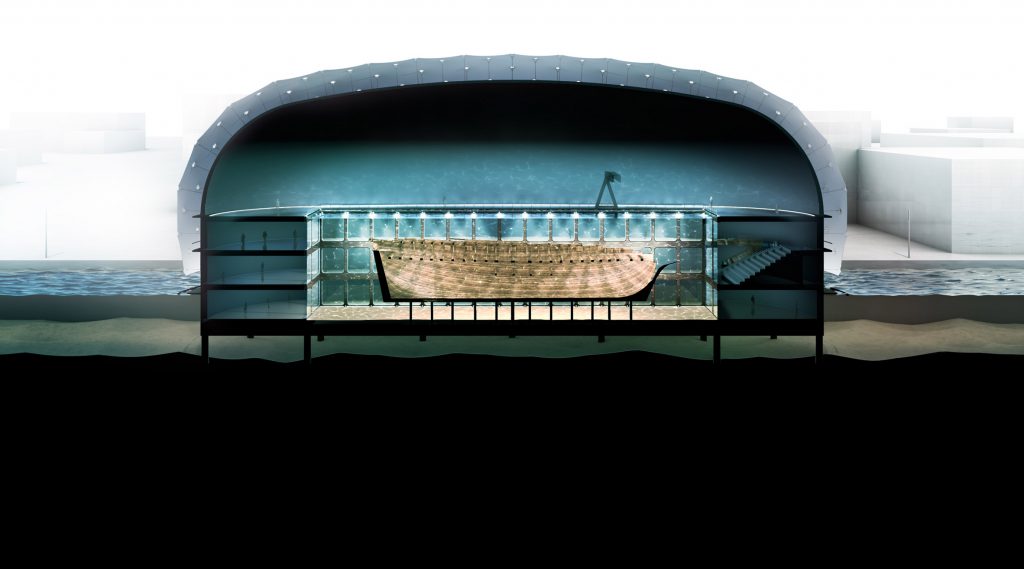

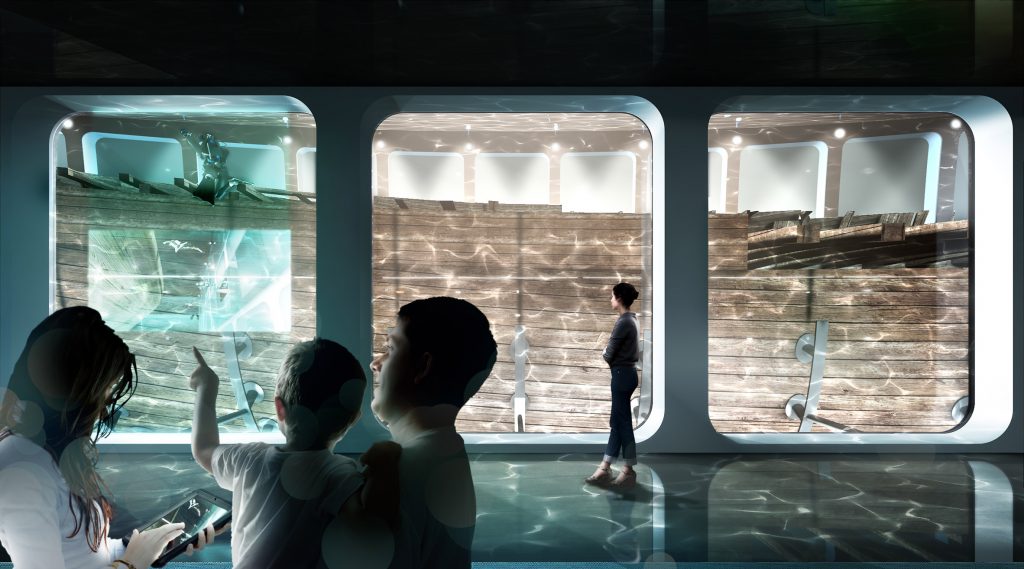

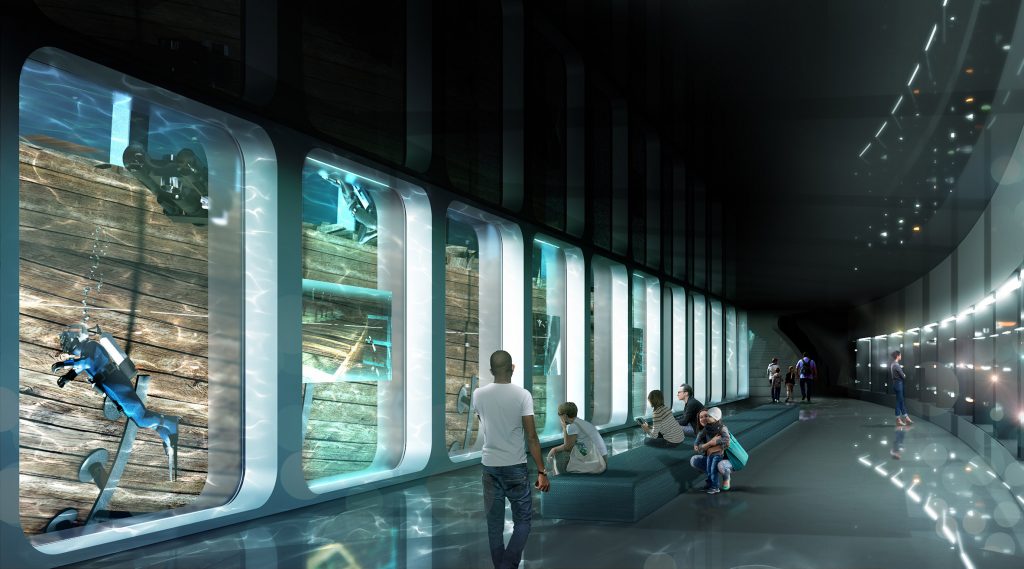

Docking the Amsterdam by ZJA

First – and obvious – reason to build under water is to showcase something that has been hidden under the sea and cannot be recovered from the seabed. Architecture studio ZJA was approached by the Docking the Amsterdam Foundation led by Amsterdam city archaeologist Jerzy Gawronski for a concept for a museum in the Netherlands to house the wreck of the historic ship, which is currently sunk off the coast of Hastings, UK. Named Amsterdam, the ship originally built in the 18th century by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) sunk back in 1749. The vessel was engulfed by sand, which let its hull and contents remain intact, although is exposed superstructure was destroyed.

Docking the Amsterdam by ZJA

The museum has been commissioned to save the 40-metre-long shipwreck from an unsafe site with a huge tidal range preventing it from any further erosion and create facilities for archeologists to shed light on Dutch maritime history.

Docking the Amsterdam by ZJA

In response, the architects have proposed to relocate the ship without taking it out of water and build the museum around a glass tank containing its remains for the visitors to observe it from several angles and watch “live excavating” of the ship by diving archaeologists. Above water, the museum will be topped by a curved canopy made from white tensile fabrics, described by ZJA as a “protective blanket”.

Docking the Amsterdam by ZJA

To relocate the Amsterdam safely, it will be lifted from the seabed using a large basin, or salvage dock, made from steel. This structure will also extract some of the water and sand surrounding the ship. The basin will then be sailed to Amsterdam. There it will be permanently docked and transformed into an underwater museum that will include exhibition spaces dedicated to the history of VOC, focusing primarily on its involvement in slavery and the impact of this on today’s society.

Docking the Amsterdam by ZJA

The exact place for the museum is yet to be decided and the project is expected to take several years, with 2025 the slated date for the basin’s opening.

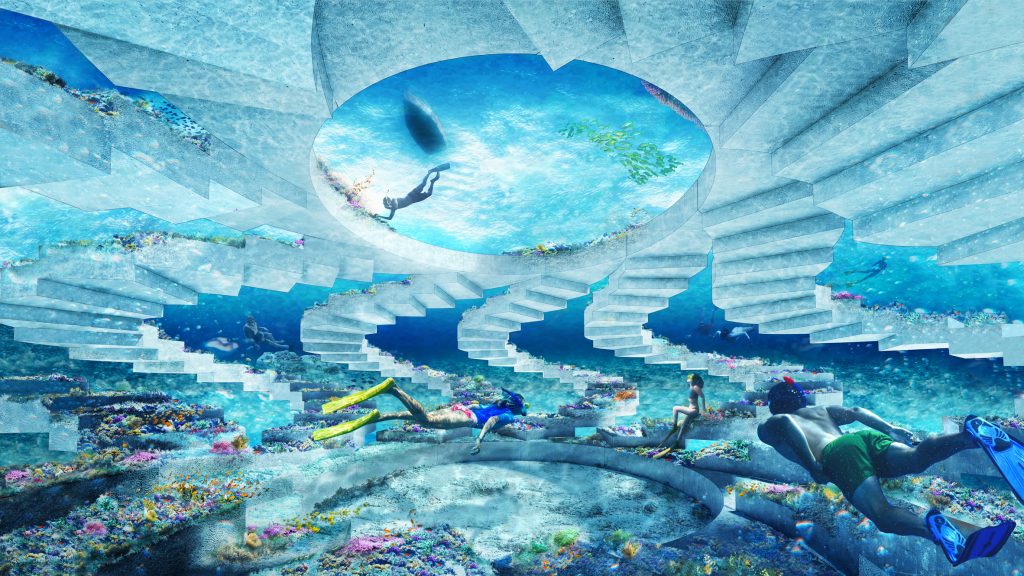

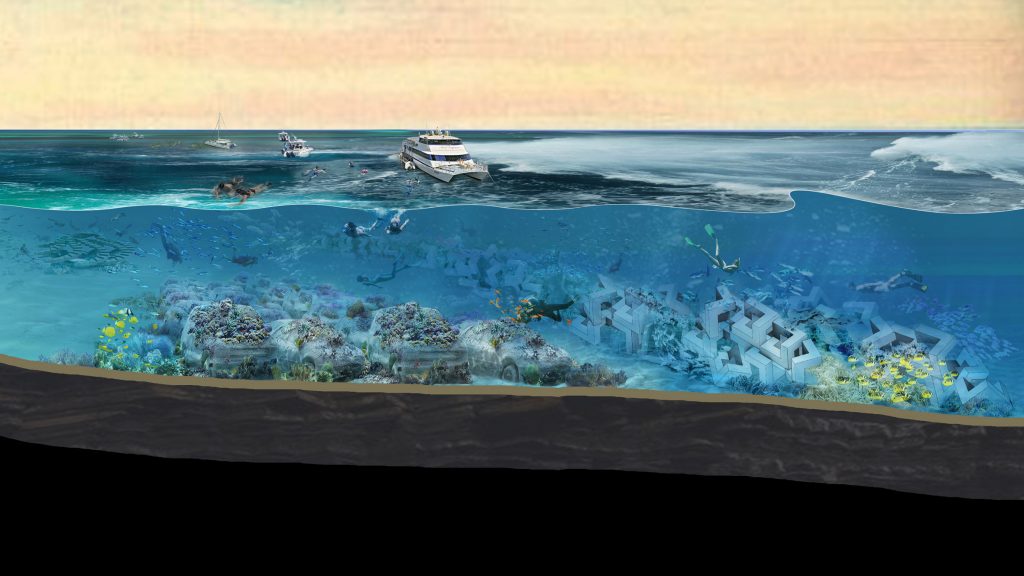

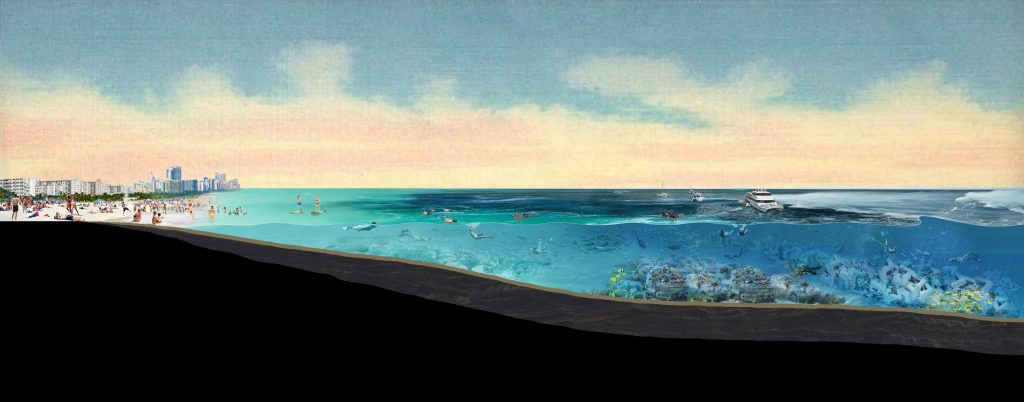

ReefLine by OMA (also header image)

While Docking the Amsterdam seeks to start discussion on the history of colonialism and slave trade, architecture firm OMA addresses the problem of the climate change. OMA partner Shohei Shigematsu, who heads the firm’s New York office, is leading the masterplan project of the ReefLine, the first underwater public sculpture park on the shoreline of Miami Beach, USA.

ReefLine by OMA

Initiated by Argentinian curator Ximena Caminos and developed in collaboration with Coral Morphologic and University of Miami researchers, the project will function as an eleven-kilometer-long artificial reef to protect and preserve the city’s marine life and costal resilience and provide a critical habitat for endangered reef organisms, promoting biodiversity and enhancing coastal resilience. In such a way, the team that includes marine biologists, researchers, architects and coastal engineers hopes to raise awareness of the way climate change is causing rising sea levels and coral reef damage in the coastal city.

ReefLine by OMA

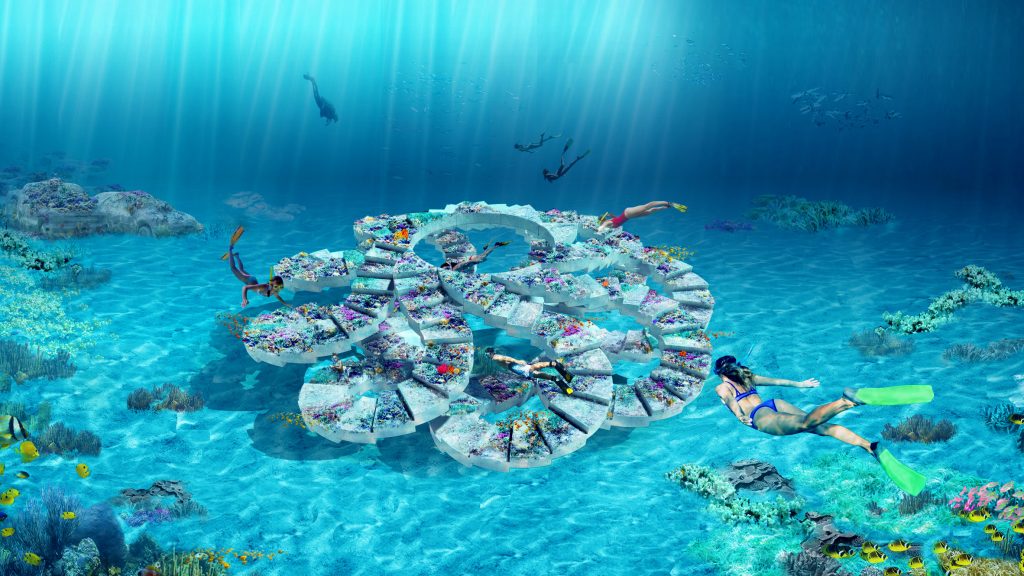

For the masterplan, Shigematsu has designed a geometric, concrete modular unit that can be deployed and stacked from south beach to the north, following the topography of the seabed. This will be punctuated by a series of site-specific installations that can only be viewed while snorkeling.

ReefLine by OMA

The artist-designed and scientist-informed sculpture park will be completed in phases, starting with a permanent site-specific installation by argentine artist Leandro Erlich who will create an underwater version of his popular sand-sculpted Traffic Jam and a sculpture by Shohei Shigematsu/OMA comprising a series sinuous spiral stairs that explores the nature of weightlessness underwater.

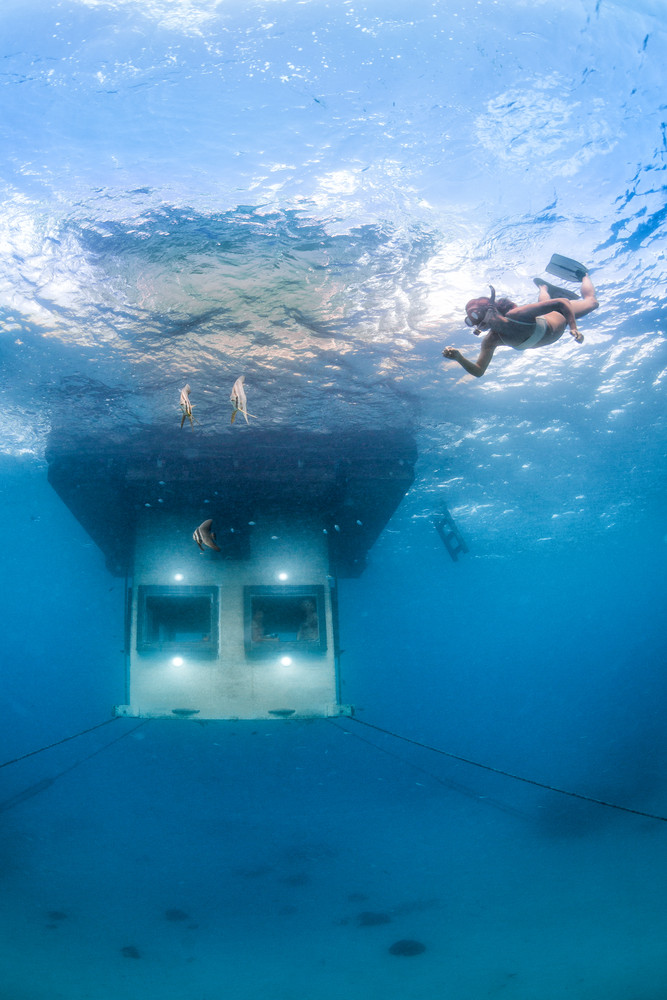

Manta Underwater room

The guests of an all-inclusive underwater hotel room at the Manta resort situated off the eastern coast of Africa by Tanzania’s Pemba Island will find themselves encapsulated within a turquoise blue bubble submerged four meters below the surface of the ocean with its coral reef and tropical marine life. Designed by Swedish company Genberg Underwater Hotels back in 2013, the floating structure provides three levels, each an experience in itself.

Manta Underwater room

The landing deck clad in local hardwood, at sea level, has a lounge area and bathroom facility. A ladder leads up to the rooftop terrace, which has a lounging area that can be used for sunbathing by day and stargazing by night.

Manta Underwater room

Downstairs is an underwater hotel room below surrounded by panes of glass for a 360 degree marine panorama. By night, the bottom platform is illuminated with underwater spotlights beneath each window, attracting a variety rare marine creatures. Coral is already establishing itself on the anchoring lines and around the underwater structure.