It has been estimated that about two-thirds of fish is discarded as waste, creating huge economic and environmental concerns. This makes product designers and researchers find creative ways to repurpose fish by-products into durable and sustainable materials instead of throwing them away.

MarinaTex by Lucy Hughes

University of Sussex graduate Lucy Hughes used fish waste to create MarinaTex, a translucent and flexible bioplastic that serves as a great compostable alternative for single-use packaging, such as bags and sandwich wrappers. According to the designer, the bio-material boasts a higher tensile strength than LDPE (low-density polyethylene), the current most common material for plastic bags, which “shows that the sustainable option does not sacrifice quality”.

MarinaTex by Lucy Hughes

The bio-plastic is made from fish scales and skin, waste products that would generally end up in landfill or be incinerated. It is low energy to produce and, unlike many other biodegradable plastics, does not require the establishment of a separate waste collection infrastructure for its disposal. Another environmental benefit of the material is that when no longer needed would break down in home composts or food-waste bins in 4 to 6 weeks.

MarinaTex by Lucy Hughes

The designer claims that the waste from just one Atlantic cod is enough to produce 1,400 MarinaTex bags. It is really impressive, if you think of 500,000 tonnes of waste that is produced in the UK annually through fish processing, according to the UK Sea Fish Industry Authority.

MarinaTex by Lucy Hughes

The MarinaTex material, which Hughes developed as her final-year project for the product design course at the University of Sussex, was the result of more than 100 experiments, which she carried out on the kitchen stove in her student accommodation. The result won Hughes UK James Dyson Award for student design back in 2019.

Pirarucu skin by Oskar Metsavaht (also header image)

Brazilian designer and founder of fashion brand Osklen Oskar Metsavaht has developed a sustainable fish skin material, which can be used as an alternative to conventional leather for garments and accessories. The new material is made via repurposing wasted skin of pirarucu fish found in Amazonian rivers and lakes.

Pirarucu skin by Oskar Metsavaht

Production of bovine leather is unsustainable and harmful to the environment, to say nothing or ranching being one of the main reasons of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. Using pirarucu skin, on the contrary, helps solve the issue of fish waste – although the fish is very popular among people in the north of Brazil for centuries, the skins are normally discarded.

Pirarucu skin by Oskar Metsavaht

Osklen buys the fish skins exclusively from communities that work alongside sustainably managed fisheries and then transports them to a tannery, where they are processed and treated. The scaly material is handmade by local artisans, which helps generate extra jobs and income for the fishermen and their families, thus bringing positive social impact, alongside an environmental one. Besides, the skin is economic to produce.

Pirarucu skin by Oskar Metsavaht

Pirarucu skin turns out to be more resilient than leather, while being softer and thinner, which makes it a perfect choice for “new luxury” goods that see a lot of use, such as jackets, shoes, wallets, and handbags.

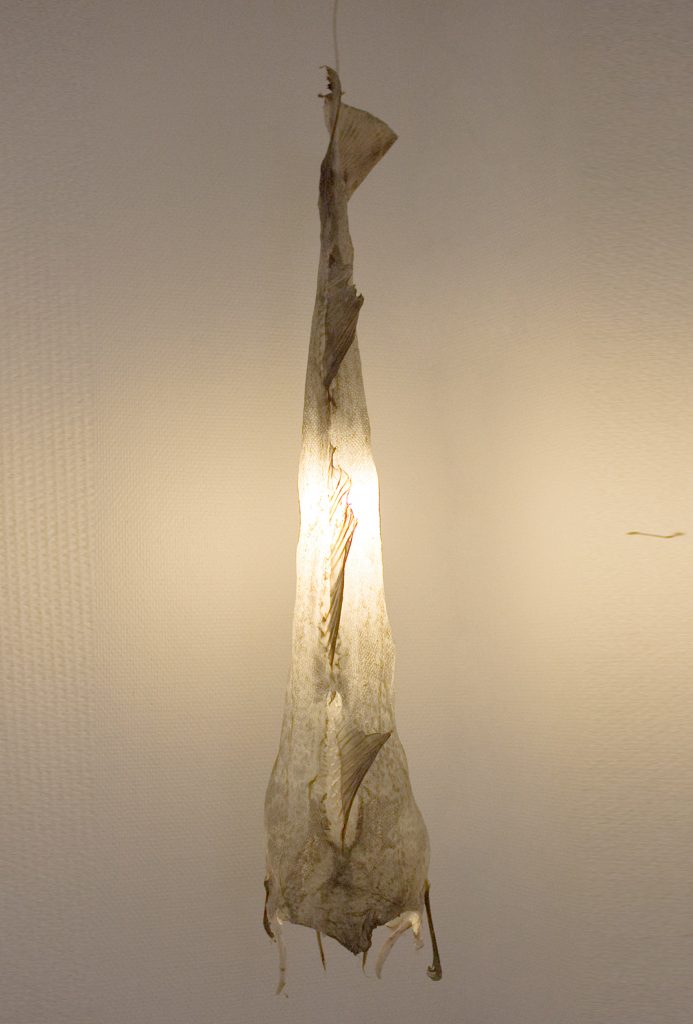

Uggi Lights by Fanney Antondsdóttir and Dögg Guðmundsdóttir

Aiming to reflect their heritage and cultural identity, Icelandic duo – Oslo-based artist Fanney Antondsdóttir and founder of Copenhagen-based brand Dögg Design Dögg Guðmundsdóttir – have turned to the vernacular traditional method of preserving fish to create the Uggi series of lamps. Originally established by the Vikings, the technique is still used in rural areas to prepare Harðfiskur, a popular Icelandic snack and export product.

Uggi Lights by Fanney Antondsdóttir and Dögg Guðmundsdóttir

Antondsdóttir and Guðmundsdóttir skin large cods, which measure over a metre in length, by hand and reshape them in an original form. The skin is then hung up to dry in the open air, while the fish continues its journey through the fish factory. The final step is the installation of lamps inside the dried skins. Since the duo started to work with this method of preserving fish back in 2001, the lamps have already proven to last for many years.