Make love, not war. This popular ippie motto can be applied to any of these extraordinary projects that seek to give new meaning to former military objects, such as old war bunkers. With this post, we continue our exploration of outstanding designs that trigger sustainable bunker experiences with respect for our history and nature.

Trilateral Wadden Sea World Heritage Partnership Center by Dorte Mandrup

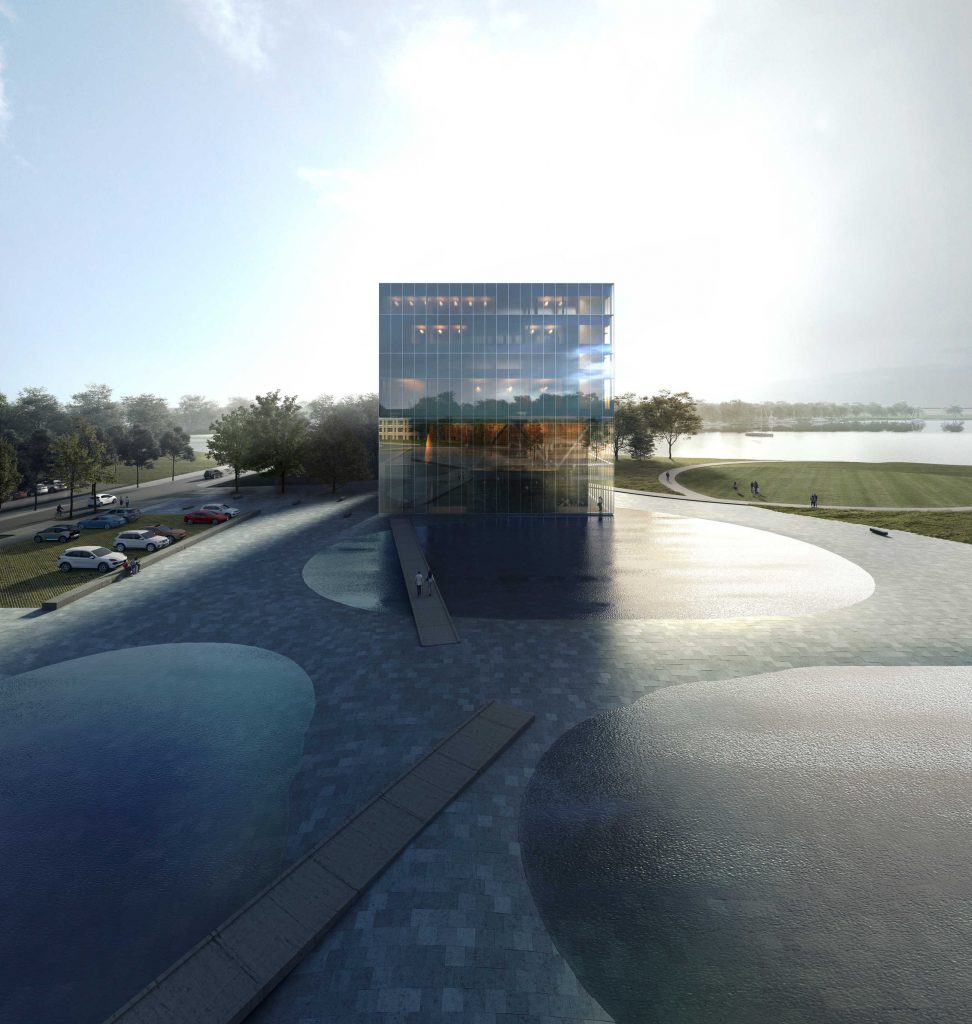

Danish architect Dorte Mandrup’s proposal to use a former military bunker as a building foundation has won a competition for a new headquarters for the Trilateral Wadden Sea World Heritage Partnership Centre, an organisation jointly run by Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. The foundation aims to protect the Wadden Sea area, the world’s largest unbroken system of intertidal sand and mud flats, which is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2009.

Trilateral Wadden Sea World Heritage Partnership Center by Dorte Mandrup

Around 1850, the area was established as a Prussian naval base, which grew to become Wilhelmshaven. The town sustained heavy bombing during World War II and today, there are only a few remains of the naval quarters with just a single, unmovable bunker appearing as a gigantic rock on the seabed. The architect decided to integrate the heavy fortification into the new structure using it as a natural anchoring point on the otherwise open field.

The primary construction is a steel frame, which will surround and heighten the existing structure, encased in a transparent glass layer, which aims to highlight the historical importance of the site and demark a transitional zone between inside and out.

Trilateral Wadden Sea World Heritage Partnership Center by Dorte Mandrup

The existing structure will be topped by four storeys of meetings and conferences facilities, storage, and offices, with a common sheltered terrace overlooking the Wadden Sea on the building’s roof. The bunker will be used for exhibition space and its roof will be reinvented as an internal courtyard, ensuring daylight throughout the building. At night, the space will be illuminated acting as a lighthouse, while in the daytime it will resemble the reflective surface of the Wadden Sea.

International Wine and Spirits Museum by Shanghai Godolphin

China-based wine lifestyle consulting and design firm Shanghai Godolphin has chosen an old military bunker as a foundation for their unique industrial style project, which houses the International Wine and Spirits Museum.

International Wine and Spirits Museum by Shanghai Godolphin

Originally built over 80 years ago to store national treasures for safekeeping during war time, the freestanding bunker was strategically placed inside the Chenshan mountain due to the cave’s internal fresh water lake, previously quarried out by the British.

International Wine and Spirits Museum by Shanghai Godolphin

The project mixes raw military functionality with the luxurious experienciality one would expect of such an institution. To visually symbolize the structure’s gradual transition from one function to another, the architects have used undulating installations made from repurposed wine crates meandering along raw cement brick walls.

International Wine and Spirits Museum by Shanghai Godolphin

Repurposed wine crates, lined in multiple rows along arching hallways of the bunker, are also used to showcase the museum’s exhibits. The arrangement creates an illusion of almost endless corridors, which encourages visitors to further explore the depths of the museum.

International Wine and Spirits Museum by Shanghai Godolphin

Heavy metal doors lead to a private cellar area that accommodates an intimate wine tasting room. Lit by candles suspended overhead, the room features a large marble table and high backed wooden chairs.

TIRPITZ Museum by Bjarke Ingels Group (also header image)

Another World War II bunker has been converted by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) into an expansive cultural complex on the shorelands of Blåvand in Western Denmark. Named TIRPITZ, the 2,800 sqm museum houses underground gallery spaces, exhibition areas and an events venue.

TIRPITZ Museum by Bjarke Ingels Group

Aiming to create an antithesis to the military object, the team chose to counterpose the inviting lightness and openness of the architecture to the to the Nazi fortress’ concrete monolith and hermeticity. From the outside, the museum looks like a series of precise cuts in the landscape.

TIRPITZ Museum by Bjarke Ingels Group

Only approaching the site, visitors notice finer slices and narrow paths descending to meet in a central clearing, bringing daylight and air into the heart of the complex. This central courtyard allows access into the four sunken galleries that are literally carved into the sand. Nevertheless 6 metre tall glass panels ensure enough daylight to naturally illuminate the space.

TIRPITZ Museum by Bjarke Ingels Group

The material palette of the project includes four main materials — concrete, steel, glass and wood — which draw from the existing structures and landscape of the area.