We just can’t get enough of beautiful brickwork. This ages-old sustainable material that was once the embodiment of something solid and impenetrable now allows architects to create living spaces that feel bright and airy. The brick patterns give birth to one-of-a-kind aesthetics of raw textures, bright red hues and the ever-changing interplay of shadow and light.

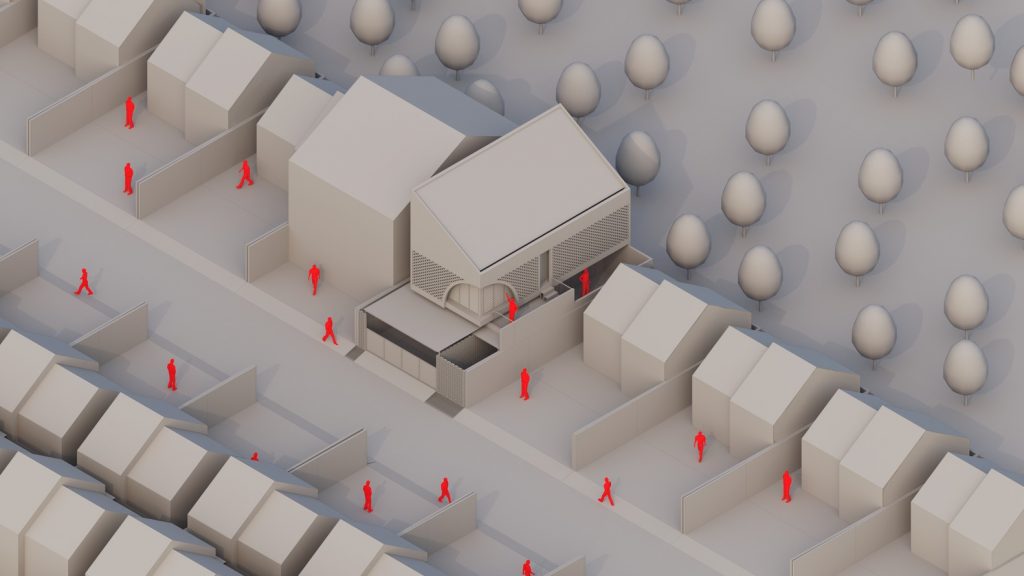

Wall House by CTA (also header image)

When Ho Chi Minh City-based CTA, also known as Creative Architects, were approached by a multi-generational family who wanted a two-storey residence in the city of Bien Hoa, Vietnam, one of the most important parts of the briefing was to design a light and airy house that would be able to ‘breathe’ 24/7 by itself. The idea of building from perforated bricks, that allow fresh air and natural light to filter in from the outdoors, naturally came to mind to the architects of the studio.

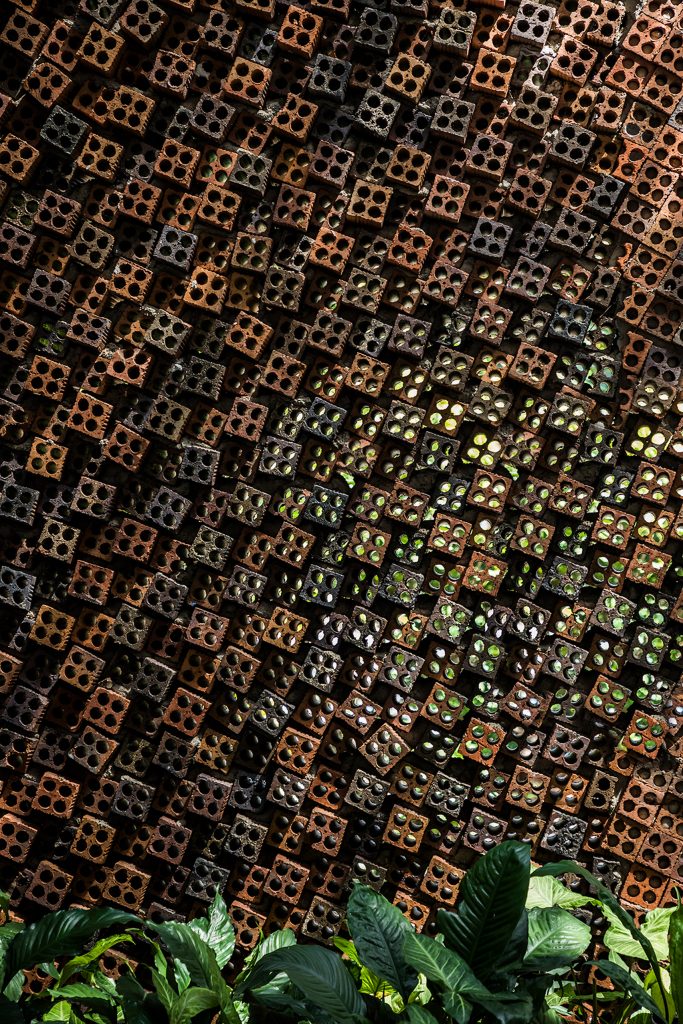

Wall House by CTA

The square bricks for the Wall House were salvaged from the building sites of properties nearby. The bricks were punctuated to feature four holes, and then arranged in an irregular stacked formation. Burnt and blackened bricks were used to add dark patches of colour into the pattern.

Wall House by CTA

The main entrance is accessed with a wide flight of tiered stairs printed with a pattern that matches the bricks on the facade. Sunlight seeps inside through the apertures in the brickwork as weel as through the house’s glass roof. A small garden of plants and trees surrounds the room to enhance the sense of outdoors.

Vinod residence by Murali Architects

A dynamic brick façade that wraps the exterior of Vinod residence in the city of Coimbatore, India, designed by Murali Architects, an innovative design practice in Tamil Nadu, combines both a regular grid formation and intricate patterns. The brickwork extends to the interior of the house cladding most of the inner walls.

Vinod residence by Murali Architects

The three levels of the residence are connected via open courtyards and glass flooring, which allows natural sunlight entering through skylights filter inside. The ground floor accommodates a living room and a kitchen, as well as a swimming pool and a central courtyard. The mezzanine level includes a guest room and an entertainment room, while the upper level features a master bedroom with a landscape courtyard and private balconies on either side, and a child’s bedroom with an elongated bay window and an inclined wall.

Elora House by Atelier Bertiga (ph: Ernest Theofilus)

Eye-catching appearance that would make the building stand out among surrounding houses alongside healthy air circulation and natural lighting have been the main priorities according to the brief for Elora House commissioned by a family of four from Jakarta-based Atelier Bertiga. It is only natural that the practice has opted for a skin of solid void brick.

Elora House by Atelier Bertiga (ph: Ernest Theofilus)

Taking advantage of the land plot of 130 sqm, the architects have divides the building into two volumes to separate the services and garden from the main program on the west with the overall goal of maximizing land area. The first mass is placed on the west side of the land to cover the sun’s heat from the west, while the second one is placed on the southeast.

Elora House by Atelier Bertiga (ph: Ernest Theofilus)

This brick façade equipped with a louver glass behind it helps reduce the heat entering from the east during the day and enables natural air circulation in the residence. By using the chimney effect, the incoming natural airflow is forwarded through the void in the middle. Hot air then exits through the wall gap in the roof to maintain the room temperature into cooler state. The existence of a high void in the middle of the house is not only used to provide fresh air intake and natural lighting – in the future, vertical additions of space can be made, if necessary. For instance, a mezzanine in the master bedroom functions as a work area.

Elora House by Atelier Bertiga (ph: Ernest Theofilus)

As the building is located near an industrial area, the upper level of the main façade of the building is dominated by the dark grey brickwork that not only endows the building’s appearance with austerity and brutality but also minimizes dust for maintenance purposes. The first floor, which accommodates core spaces such as the family room, dining room, and kitchen, is clad in brighter and contrasting terracotta bricks. The architects left rooms on the lower level deliberately exposed to a garden shaded by lee kwan yeu vines to show the connection between the outside and the heartwarming interior.