Construction industry accounts for a large proportion of greenhouse gas emissions, one of the main reasons of climate crisis. Today, many architects address this issue turning to carbon-neutral buildings, when carbon emissions are minimised at all stages, including the manufacturing processes, during construction and use. Carbon-neutral buildings, which feature climate-positive initiatives so that the net carbon footprint over time is zero, are becoming more common.

Centennial College by Dialog and Smoke Architecture

Two architecture firms from Canada – Dialog and Smoke Architecture – have collaborated to design Canada’s “first-ever mass timber, net-zero carbon, higher-education facility”. The project, called A-Block Building Expansion, is a 13,935 square metres addition to the existing building at Centennial College of Applied Arts and Technology. The six-storey extension will be constructed with cross-laminated timber (CLT) manufactured using locally sourced wood.

Centennial College by Dialog and Smoke Architecture

As well as the use of wood, which traps carbon, to get the carbon-neutral status, the structure will also feature photovoltaic panels on its rooftop and produce enough energy on-site to offset the annual greenhouse gas emissions associated with construction operations.

Centennial College by Dialog and Smoke Architecture

The team claims that the concept of the building is heavily informed by designs from Canada’s Indigenous peoples, also known as First Nations, and is rooted in the idea of Two-Eyed Seeing from Albert Marshall, an Elder of the Mi’kmaw Nation, that to help support reconciliation with Inuit and Metis peoples.

Centennial College by Dialog and Smoke Architecture

Externally, the L-shaped building will be clad in aluminium shingles and feature a geometric pattern with windows of different shapes, which is an allegorical response to Ingineous arts and crafts. Exposed wood pillars and beams inside will showcase the underlying structure. Inside are other details of Indigenous art, one of which is a multipurpose room in the centre shaped like a wigwam and called Indigenous Commons.

Hotel Bauhofstrasse by Von M

Stuttgart-based architecture studio Von M has completed a hotel that was commissioned to be the first CO2-neutral building in Ludwigsburg, Germany. Although the building’s base and staircase are made from concrete, which is carbon-intensive, the team managed to compensate that by the use of wood for the structure as well as load-bearing elements in order to make the building more sustainable.

Hotel Bauhofstrasse by Von M

CLT modules were computer-controlled cut from local wood, furnished with the necessary additions such as windows, floor coverings and tiles in a production hall assembly line, and pre-assembled in the factory in Austria. They were then shipped to the construction site in the city centre and installed over five days.

Hotel Bauhofstrasse by Von M

However, when observed from the outside, there is not a single hint it is a wooden building. Externally, it is clad with white fibre cement shingles that give the façade a distinctive appearance contrasting against the existing environment with its baroque castle and a 1970s shopping centre. According to the architects, this cladding, together with the flush-mounted standing window formats and dormers, shrewdly translocate the local building traditions into our time.

Hotel Bauhofstrasse by Von M

Inside, the concrete surfaces have been left exposed, and the cross-laminated timber boards unpainted, which matches the overall neutral colour palette of beige, grey and white.

Science Center in Lund by COBE

COBE, the Danish architecture firm led by Dan Stubbergaard, is going to build a fully carbon-neutral building for a new science center in the Swedish university city of Lund. Scheduled to open in 2024, the new structure will form part of ‘Science Village Scandinavia’, a new urban district that will also host the ESS (European spallation source) and MAX IV — advanced research facilities within neutron and X-ray research.

Science Center in Lund by COBE

The two-storey wooden building will contain exhibition halls, a gallery, a reception area, workshops, a museum store, a restaurant, offices, and an auditorium. Just like many other sustainable and climate-friendly buildings, the structure will be constructed using prefabricated CLT components. According to the architects, it will be heated with excess heat from ESS through a so-called ‘ectogrid’ system, where warm water is passed through local heat pumps and eventually used to heat the building.

Science Center in Lund by COBE

The 1,600-square-meter roof, which also serves as a rooftop patio and viewing platform, comprises a large energy park. In addition to the solar cells, which cover the whole roof and provide enough energy to make the institution self-sufficient, there are energy bikes visitors can use generate electricity through pedal power.

Science Center in Lund by COBE

In the large, round atrium, which is open to the public, the building is bisected by a green path where plants, flowers, and trees attract insects also help absorb carbon dioxide.

Powerhouse Telemark by Snøhetta (also header image)

Meanwhile, Snøhetta has completed Powerhouse Telemark office in Norway, which goes one step further and is described as carbon-negative. As the description suggests, the building is supposed to produce more energy than it will consume over its lifespan. This will be achieved by the use of a large photovoltaic canopy covering its roof and south-facing façade. According to the team, the solution will generate 256,000 kilowatts of energy each year, which is enough surplus renewable energy to compensate for the carbon consumed by the office over a 60-year lifespan – including its construction, demolition and the embodied-carbon of building materials.

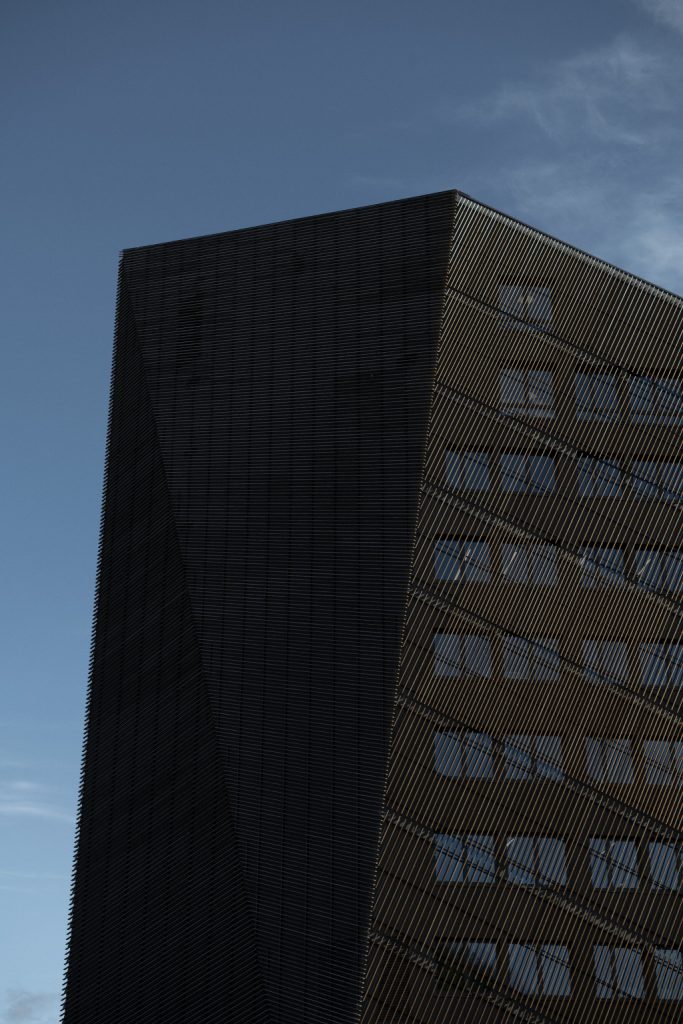

Powerhouse Telemark by Snøhetta

The angular 11-storey building features a steep roof that helps to maximise the amount of solar energy the photovoltaic canopy can harvest and creates light-filled spaces inside, where artificial lighting is used at an absolute minimum.

Powerhouse Telemark by Snøhetta

The building’s facades are highly insulated and clad in a mix of wooden panels used as solar shading and large fibre cement sheets that can store thermal heat during the day and slowly emit heat in the evening. Together with a system that uses geothermal wells dug 350 metres below ground, this helps to passively heat and cool the building.

Powerhouse Telemark by Snøhetta

Inside, the building includes flexible, co-working spaces, smaller and more traditional workspaces, as well as a “barception”, a shared staff restaurant, penthouse meeting spaces and a roof terrace. Their layout is designed to reduce overheating and dependence on artificial cooling.

Powerhouse Telemark by Snøhetta

The building’s structure is made from ‘environmental concrete’ that uses less energy in its production and produces less carbon dioxide than traditional concrete. To reduce the amount of concrete required for the project, the building does not include a basement.