A classic labyrinth is a primal architectural typology. On the one hand, it puts the creator in the position of power letting them direct the movements of the visitor to an absurd extent. On the other hand, being composed of just walls, it appears to be an essential form of architecture. Contemporary designers and architects get inspired by the form interpreting it in symbolical installations that make one contemplate on art, environment, or even truth.

The Labyrinth by the Belgian studio Gijs Van Vaerenbergh was exhibited in 2015 at the heart of the C-mine arts centre in Genk, Belgium. The work explored the age-old form of the labyrinth as a spatial experience, a unique composition of wall and void.

Labyrinth by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh. Ph: Filip Dujardin

The site-specific installation included a collection of frames made of 5mm steel plates weighing a total of 186 tons. The architects Pieterjan Gijs and Arnout Van Vaerenbergh state that a series of Boolean transformations generated openings and perspectives on the environment, which became points of orientation throughout the journey and gave the labyrinth a new meaning.

Labyrinth by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh. Ph: Filip Dujardin

The ascension of the mine shafts nearby was included in the experience in order to create another interesting relationship with the environment. This let one witness the structure and the wandering visitors from above – i.e. from the point of view that is usually only reserved for the creator of the labyrinth. Showing the Labyrinth as a sculptural whole, this perspective ran against what a labyrinth should do: conceal itself, which loads the artwork with symbolical meaning.

Victoria Pragensis by Juras Lasovsky. Ph: Jakub Nedbal

In 2018 Czech-born architect Juras Lasovsky created the Victoria Pragensis installation in collaboration with Haenke and National Theatre in Prague to emphasize the precious yet fragile cultural heritage of medicinal plants, and their role in the context of public spaces and urban design. The green structure paid homage to Victoria Amazonica, the world’s largest water lily, first discovered in 1801 by Czech botanist Thaddaus Haenke.

Victoria Pragensis by Juras Lasovsky. Ph: Jakub Nedbal

Nearly a thousand of plants were exhibited in levitating white pots set on metal frames of various heights, which referenced trunks in a wood and were placed so that the whole topography descended towards the center of the installation – here its level was at its lowest, creating an allegoric meadow. Designed in the form of a labyrinth evolving from the square grid, Victoria Pragensis led the visitor to its center where the plants absorbed them entirely as a temporary landscape within an urban space.

Truth Always Appears As Something Veiled by Hector Zamora. Ph: Iñaki Bergera

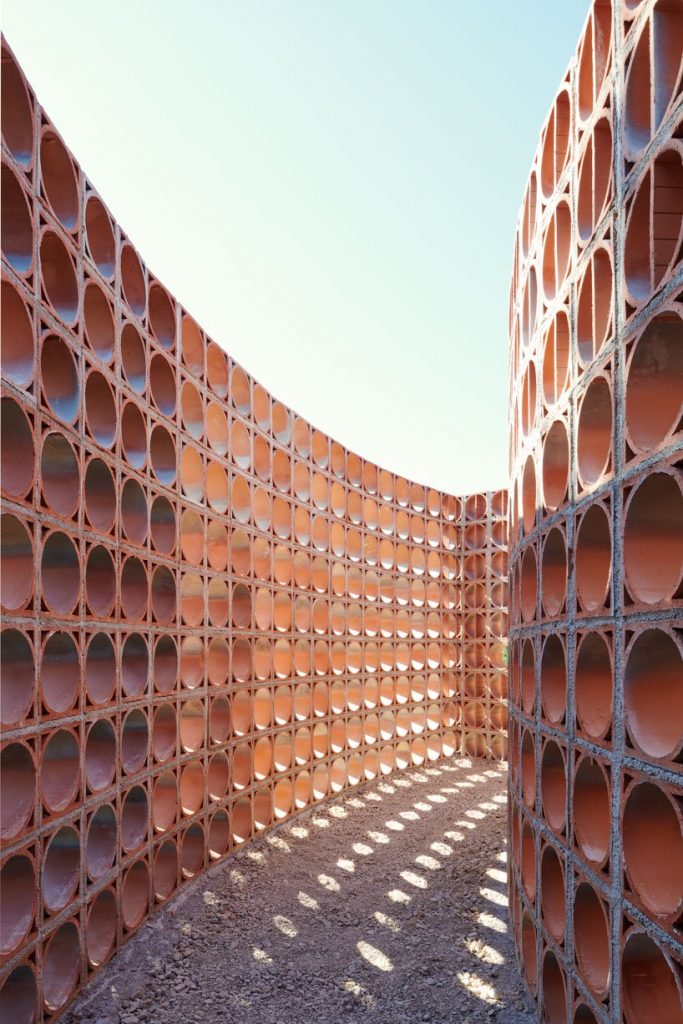

This summer Mexican artist Hector Zamora exhibited a maze-like brick structure entitled Truth Always Appears As Something Veiled as part of the Solo Houses ‘Summer Group Show’ – the initiative by Eva Albarrán and Christian Bourdais who encourage artists to experiment with large scale work that needs open-air space.

Truth Always Appears As Something Veiled by Hector Zamora. Ph: Iñaki Bergera

The project is inspired by the ancient Knidos labyrinth found on a block of black marble in the ruins of the Roman city. Unlike intricate networks of Western mazes, the project encompasses a single circular route which leads toward its center and returns with no alternate options or shortcuts. As the name of the artwork suggests, in opposition to the majority of mazes, the structure has semi-translucent walls of perforated brick that obstruct the view only partially, which draws visitors inside in search of the center as in search of elusive truth.