One of the oldest building materials known to man, bricks are perceived today in a new light. Architects take this humble and eco-friendly material to create a new contemporary aesthetics. Visually, intricate brickwork produces an ever-changing geometric pattern of light and shadow on the walls and floors. Simultaneously, perforated brick façades make the building more sustainable and energy-efficient, as they allow air flow in and out to regulate temperature within the home keeping harsh sunlight, noise and dust from entering the living spaces.

Krushi Bhawan by Studio Lotus

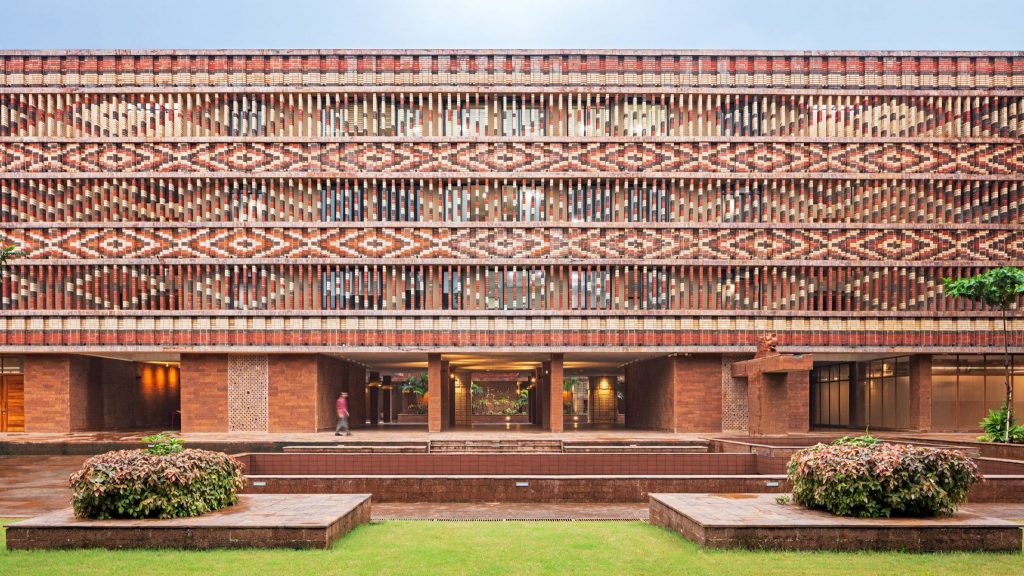

Designed by New Delhi-based architecture practice Studio Lotus, Krushi Bhawan is a complex of administrative offices for the Department of Agriculture & Farmers’ Empowerment in Odisha, India, which illustrates how a government facility can extend itself to celebrate local context, craftsmanship and sustainability and become a vital part of the social infrastructure.

Krushi Bhawan by Studio Lotus

The project comprises a learning centre, library, auditorium, training rooms, garden and a public plaza, while the offices for 600 staff have been moved to the upper floors making it possible to keep most of the other facilities open to the public even on holidays. The rooftop too has been conceived as a public demonstration of urban farming.

Krushi Bhawan by Studio Lotus

Regional materials and techniques feature all over Krushi Bhawan adapting local motifs to an unprecedented architectural scale. The building is wrapped in elaborate brickwork. Bricks of three different colours made of locally sourced clay create a pattern designed to emulate Odisha Ikat, a traditional dyeing technique from the eponymous Indian state, its colors representing the geographical diversity of the region. The perforated façade acts as a solar shading device and helps to naturally cool the building.

Krushi Bhawan by Studio Lotus

The pedestal of the building is made from hand-carved laterite and khondalite stone from nearby mines. Khondalite is also used to create lattices around the central courtyard, which has a stone inlay floor that displays a yearly calendar according to the crops celebrating Odisha as one of the major suppliers of grain in India.

Krushi Bhawan by Studio Lotus

The plaza has an amphitheatre, and a garden with a pond to naturally cool the space. The space is accessed via a pathway lined with trees and stone colonnades. Integrating craft in a contemporary environment, the interior features handcrafted furniture, stone carvings and metalwork created using centuries-old techniques depicting local mythologies.

Using local materials lower the building’s carbon footprint, while rooftop solar panels enhance its overall sustainability.

Sharif Office Building by Hooba Design Group

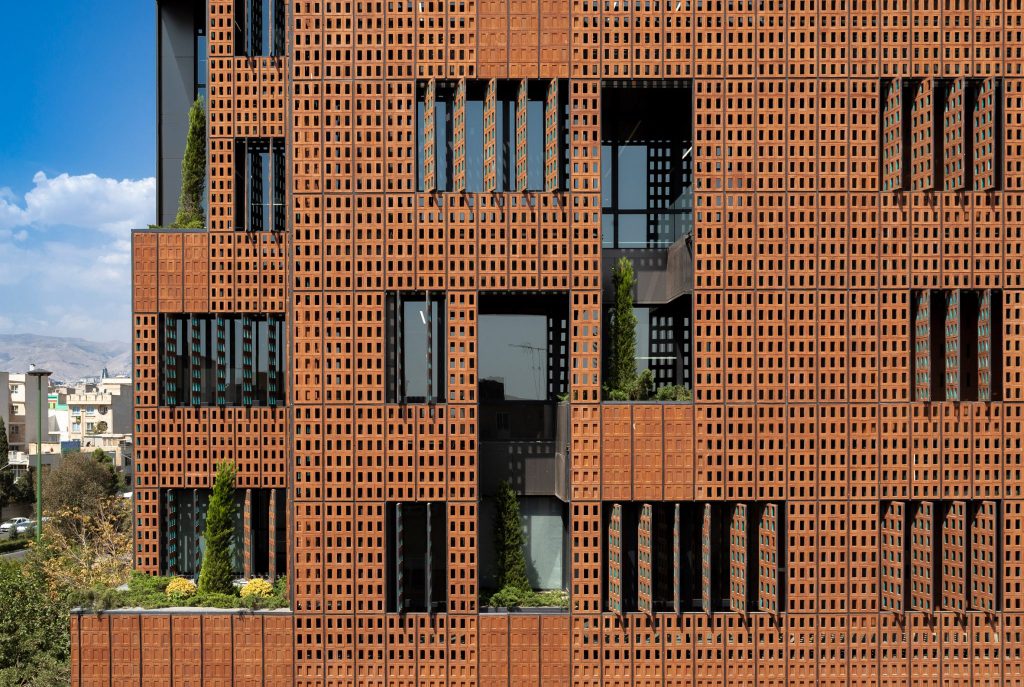

An office building for the Sharif University of Technology in Tehran, Iran, designed by the local architecture studio Hooba Design Group, features a façade of specially-made smart-brick panels that adapt to different times of the day.,

Sharif Office Building by Hooba Design Group

The bricks designed and manufactured exclusively for the project take a cue from the 1940s-style used for the nearby university buildings but are larger and have a cut-out in the middle that is the same dimension as the traditional bricks, which gives a semi-transparent character to the solid block.

Sharif Office Building by Hooba Design Group

These blocks are set on panels equipped with programmable light sensors that adjust based on lighting patterns, required light exposure in the interior spaces and user preferences. Moreover, the building’s double skin helps to control the sun heat and reduce energy consumption.

Sharif Office Building by Hooba Design Group

The 7,200 sqm building accommodates open and semi-open offices, as well as common spaces, including a research-based communal workspace, a meeting space and a cafeteria.

Camp del Ferro by AIA, Barceló-Balanzó Arquitectes, and Gustau Gili Galfetti

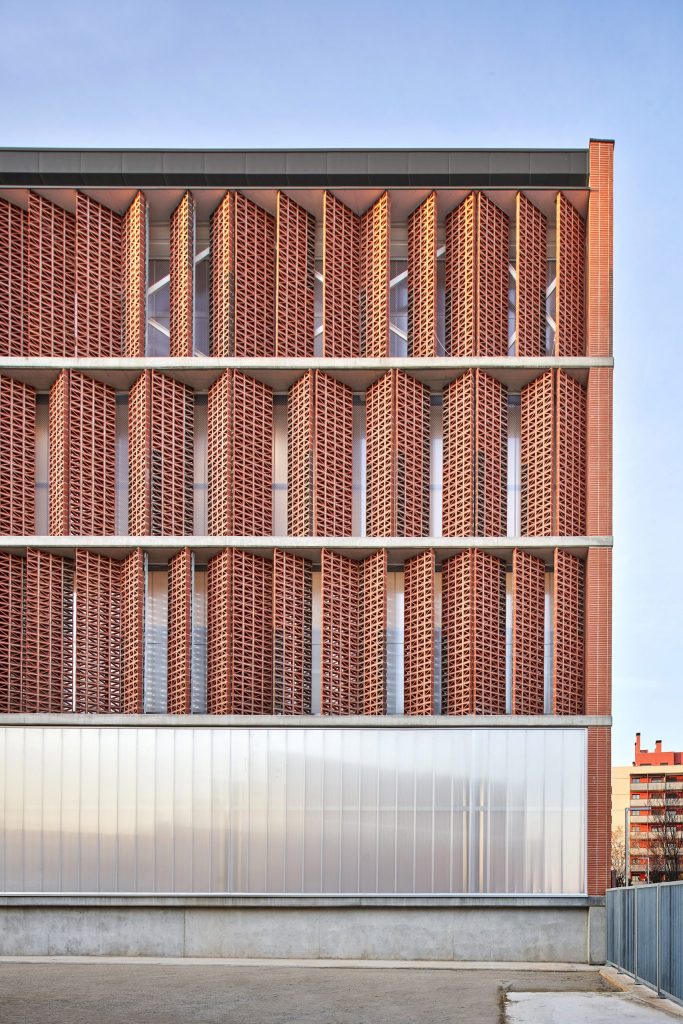

A mix of solid and perforated bricks creates rich patterns in the façade of Camp del Ferro, Barcelona sports centre, completed by local architects Albert Salazar Junyent and Joan Carles Navarro of AIA, Antoni Barceló and Bárbara Balanzó of Barceló-Balanzó Arquitectes, and Gustau Gili Galfetti.

Camp del Ferro by AIA, Barceló-Balanzó Arquitectes, and Gustau Gili Galfetti (also header image)

To pay homage to the common material in the neighbourhood, the architects has created the façade using bricks in different opacities, patterns and textures. Solid and perforated bricks in different shades create a variety of irregular patterns, helping to visually soften the massing of the building. Perforated bricks allow sunlight to filter into the three sports courts but also moderate the heat, creating optimal conditions for play. Angled sunshades are also made of the perforated bricks to reach the same effect. This, together with natural cross-ventilation and plant-covered roof, helps minimize the building’s energy requirements.

Camp del Ferro by AIA, Barceló-Balanzó Arquitectes, and Gustau Gili Galfetti

A larger part of the building is sunk underground, with two of the three sport courts situated in the basement. This spatial manipulation helped reduce the visual perception of the structure’s size. The third court is located upstairs, directly above one of the submerged courts, while the roof of the other is used as an entrance plaza, thus generating an open urban space that is extended to the city. To prevent overheating, the court on the upper floor features a glazed wall.

Find more reading about outstanding perforated brick façades here.