Should jewelry be a synonym of luxury burdened with negative connotations of over-exploiting natural resources? Contemporary jewelry designers find new unconventional ways to create their items via repurposing and recycling the most unexpected materials. The resulting recycled jewelry pieces promote circular economies, help save endangered species and bring wearers closer to nature – and even give food for thought about our own mortality and vulnerability.

Erin Considine Jewelry for Lauren Manoogian

It is quite a standard practice for jewelry makers to recycle their bench sweeps. Brooklyn designer Erin Considine has handmade a jewelry series for New York brand Lauren Manoogian from scraps of sterling silver found in her studio. She has used techniques of reshaping leftover silver at a very high heat, drawing on her experience of working with steel while studying blacksmithing.

Erin Considine Jewelry for Lauren Manoogian

The designer used the flame form a torch to move the silver to a certain threshold between molten and solid, and showing the reticulated structure of the metal, and let the semi-liquid metal flow to make organic shapes. According to Considine, this is a very unconventional way of working with metal, for generally the process is tightly controlled. The resulting pieces that include bracelets, rings, earrings and a necklace have irregular shapes and edges.

Erin Considine Jewelry for Lauren Manoogian

The designer used blocks of charcoal designed for direct casting to form elements of the cuff and earrings. The charcoal being soft enough, she carved the desired shapes into the block to make the jewelry.

Erin Considine Jewelry for Lauren Manoogian

Another tool she utilized is the end of wooden chopsticks with the help of which she manipulated molten metal to create the decorative element of the choker. The sides were then created using a metalworking process known as drawing wire – in which a segment of wire is pulled through a series of dies that resemble moulds.

Jewelry made from pistachio shells by Belle Smith (also header image)

London-based jeweler Belle Smith creates her pieces using not solely precious metals – she combines them with such mundane material as discarded pistachio shells. The repurposed shells are attached to delicate necklace wire chains made from recycled silver and steel to form a wearable textile, which is then shaped into hollow spheres and tubes. The otherwise fragile shells from a single structure as a result.

Jewelry made from pistachio shells by Belle Smith

Smith was inspired by Japanese craft techniques as she experimented with different processes that celebrate flaws. Among her influences was the Japanese concept of Wabi-Sabi, which regards imperfections such as asymmetry and roughness as beautiful, and focuses on the integrity of natural objects and processes.

Jewelry made from pistachio shells by Belle Smith

According to the designer, the pieces were inspired by the “protective role” of the shells in relation to the nuts inside. Comparing them to a womb protecting ovaries, Smith describes the shells as “nature’s vessels of fertility”.

Tangible Truths by Sybille Paulsen

Berlin-based designer Sybille Paulsen also touches questions of vulnerability and fragility of the to accentuate the sensitive vessels that are our bodies. For her project Tangible Truths project, she has been working with cancer patients who leave their hair to Paulsen to transform it into a unique and personal piece of art. In this way rather than lose the hair gradually as a result of chemotherapy treatment, the women can wear it – but in a different way. According to Paulsen, in this way the change becomes visible, not only as the lost hair but further as its transformation into something valuable. In other words, something abstract – transformation – becomes tangible.

Tangible Truths by Sybille Paulsen

All of the pieces are carefully handmade in a labour intensive process that can take days or even weeks until they transform into beautiful, tactile objects telling their individual stories. The designer takes the time needed for production of a jewelry piece to know the client better. The resulting items are mostly necklaces that combine braided or loose hair with coloured wool threads, copper, brass, silver, gold and cast-resin pieces, in colours that have personal significance to the clients. These objects are conceived to be the introduction to an exchange of difficult feelings that are otherwise hard to communicate.

Tangible Truths by Sybille Paulsen

Additionally to creating an artifact for the patient, the designer also braids wristbands or necklaces for family members and close friends. “Not only the person affected, but also the people around them, pass through a transformation. The artefacts I create mark this transformation and disclose a new access for the people involved to the commonly overwhelming situation,” explains the artist.

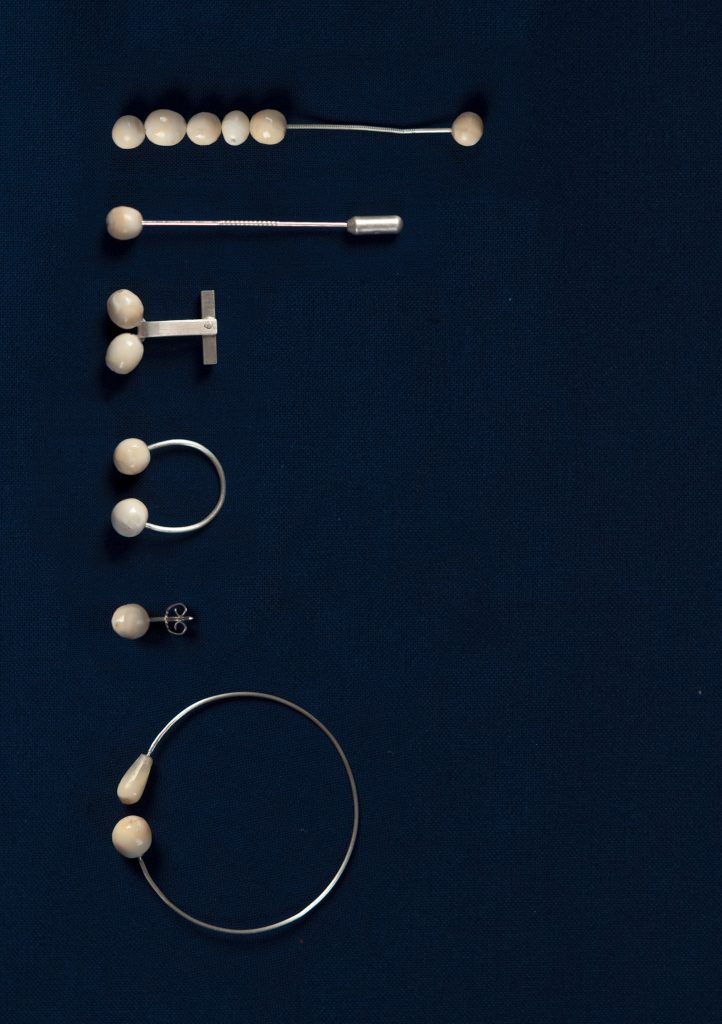

Human Ivory Collection by Lucie Majerus

Eindhoven graduate Lucie Majerus has also drawn inspiration from Japanese philosophy Wabi Sabi, which cherishes what is simple, unpretentious and aged. She creates pearls of extracted wisdom teeth for her Human Ivory collection of customized jewelry, aiming in such a way to propose an alternative to materials normally harvested from animals, such as elephants.

Human Ivory Collection by Lucie Majerus

She cleans teeth with bleach and then shape the material with a stone-polishing machine to turn it from recognisable teeth into an abstract but familiar pearl shape, and according to the designer, with this careful transformation the possible disgust associated with a human tooth evolves into attraction and beauty.

Originally, Majerus created jewelry from her own wisdom teeth and she also collected teeth from her teachers to create customized items for them. At the moments she takes commissions encouraging people to collect their own teeth over time – whether they’ve fallen out naturally, or been removed – to “adorn yourself with yourself” and think about personal and material values.

Human Ivory Collection by Lucie Majerus

The collection includes earrings, cuff links, brooches and rings. A tie pin features a single pearl of “human ivory”, while earrings are made of several ones stacked on top of one another. The simple beauty of tooth pearls is accentuated by minimal addition of metals for connection and support role.