Design has always reflected the values of its time. Today, as climate change reshapes priorities across industries, materials are becoming more than passive building blocks. They are active agents in environmental repair. Carbon-negative materials, which remove more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they emit across their lifecycle, are emerging as one of the most compelling areas of innovation at the intersection of design, science and industry. From plastics that lock away carbon to sand that grows in seawater, these materials suggest a future where making things can actively help heal the planet.

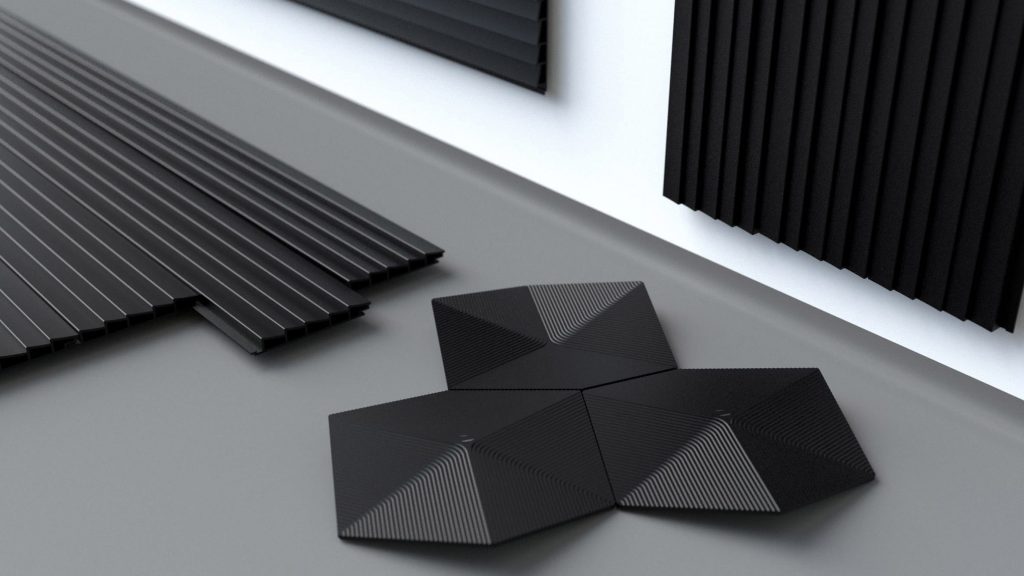

Bioplastic by Made of Air

Berlin-based startup Made of Air approaches materials with a climate-first mindset. Its flagship innovation is a bioplastic made largely from biochar, a charcoal-like substance created by heating agricultural and forestry waste in an oxygen-free environment. The result is a recyclable thermoplastic that is around 90 per cent carbon and stores roughly two tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent for every tonne of material produced. Rather than releasing emissions, the material effectively locks them away for centuries.

Bioplastic by Made of Air

Founded in 2016 by architects Allison Dring and Daniel Schwaag, the company grew out of an architectural interest in performance-driven surfaces. Their earlier work on pollution-absorbing facades evolved into a more ambitious question: what if materials themselves could help reverse climate change? As chief commercial officer Neema Shams puts it, Made of Air may be a materials company in practice, but at heart it is a climate company. By storing more carbon than it emits over its lifecycle, the material qualifies as genuinely carbon-negative.

Bioplastic by Made of Air

Crucially for designers and manufacturers, Made of Air behaves like a conventional thermoplastic. Biochar is combined with a sugar-cane-based binder and processed into granules that can be injection-moulded using standard plastic machinery. This compatibility has enabled applications across furniture, interiors, transport and urban infrastructure. Recent projects range from limited-edition sunglasses made with H&M to HexChar facade panels installed on an Audi dealership in Munich, where seven tonnes of cladding store an estimated 14 tonnes of carbon.

Bioplastic by Made of Air

Looking ahead, Made of Air’s ambitions are measured in gigatonnes. The company is rapidly scaling production, with the long-term goal of storing up to a gigatonne of CO2e annually by 2050.

Carbon-Negative Concrete Aggregates by Alessandro Rotta Loria and Cemex

If plastic is one front in the carbon battle, concrete is another, far larger one. Sand, a critical ingredient in concrete, is becoming scarce, environmentally destructive to extract and deeply carbon intensive to transport. Against this backdrop, researchers at Northwestern University have developed an artificial, carbon-negative alternative that quite literally grows out of seawater.

Led by civil engineer Alessandro Rotta Loria and developed in collaboration with cement manufacturer Cemex, the material is produced through a process known as mineral electrodeposition. By applying an electrical current to seawater, naturally occurring calcium and magnesium ions solidify into mineral structures, mimicking the way marine organisms form shells. The twist lies in injecting additional CO2 into the system, dramatically accelerating growth while embedding carbon into the resulting material.

Earlier versions of this idea, explored as far back as the 1980s, never reached scale because growth rates were too slow for construction needs. Rotta Loria’s team overcame this limitation by increasing the concentration of CO2, enabling them to grow a nine-centimetre sphere in just 30 days under laboratory conditions. While still experimental, the resulting material is structurally comparable to conventional sand and could serve as a direct replacement in concrete mixes.

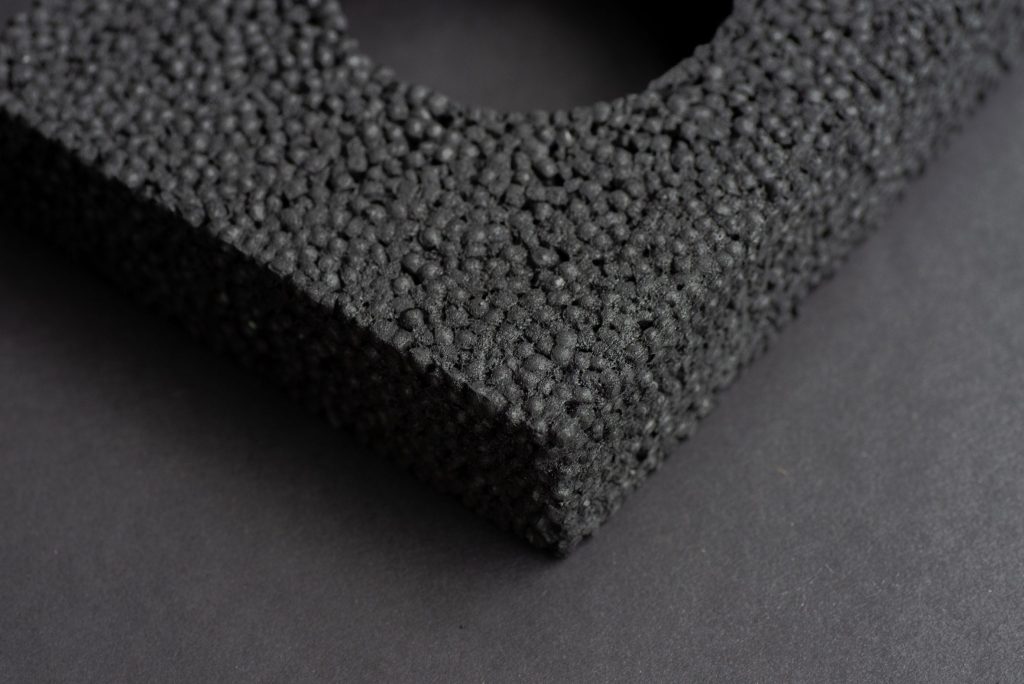

Biochar Foam by Carbon Cell (also header image)

While concrete and plastics dominate headlines, packaging and insulation represent another vast and stubbornly polluting material category. Expanded polystyrene remains widely used, rarely recycled and heavily dependent on fossil fuels. British startup Carbon Cell is offering a striking alternative: a lightweight, rigid foam made from agricultural waste that is both compostable and carbon-negative.

Biochar Foam by Carbon Cell

Visually, Carbon Cell’s foam looks familiar, with the same closed-cell structure as polystyrene, albeit rendered in a distinctive black. The similarity is intentional. Invented by scientist Elizabeth Lee, engineer Eden Harrison and designer Ori Blich during their studies at Imperial College London and the Royal College of Art, the material mirrors polystyrene’s production process. Biochar derived from crop waste is mixed with bio-based polymers, formed into pellets and then expanded using existing equipment.

Biochar Foam by Carbon Cell

The environmental difference, however, is profound. For every kilogram of Carbon Cell foam produced, nearly a kilogram of carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere. At the end of its life, the bio-based polymer degrades under home composting conditions, leaving behind biochar that continues to sequester carbon in the soil while improving its quality. What was once a persistent pollutant becomes a long-term carbon store.

Biochar Foam by Carbon Cell

Carbon Cell is preparing for pilot production, initially targeting packaging before moving into building insulation. Lee, now the company’s CEO, describes insulation as the largest long-term market, though certification and scale take time. Along the way, the team is exploring applications from acoustic panels to stage scenery, all with the goal of displacing polystyrene and related foams across industries.

Whether through biochar plastics, mineral-grown sand or compostable foams, carbon-negative materials challenge the assumption that making things must come at an environmental cost.