What do you imagine when hearing “an underground house”? To claustrophobic people that might sound extremely intimidating. However, this is a popular misconception. Energy-efficient and weather-resistant, underground homes can cut down on heating and cooling costs significantly, and they provide a peaceful and comfortable atmosphere. Check out some subterranean homes across the globe for those who prefer to live underground, literally.

House below ground level by Junya Ishigami

In the Japanese city of Ube, Japanese architect Junya Ishigami has created an unusual residence/restaurant for his old friend, a chef and French restaurant owner Motonori Hirata. The client wanted “an architecture whose heaviness would increase with time,” a building that would contain both a house and a restaurant, something he could pass on to his children and grandchildren.

House below ground level by Junya Ishigami

The extraordinary mud-covered building was crafted by pouring concrete into holes in the ground. After countless modifications, a mass model was converted into 3D coordinate data, which was then then input into a total station (TS) survey instrument to determine the points for pile driving. In the meantime, construction workers dug the hole manually for precision while constantly confirming the position and shape on an iPad.

House below ground level by Junya Ishigami

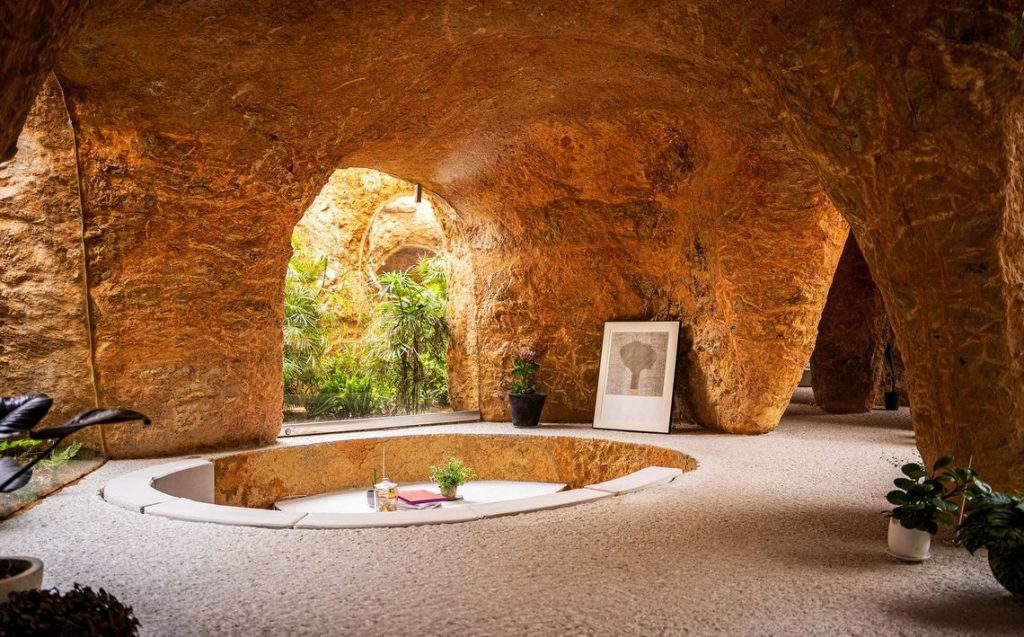

When the structure was excavated after concrete solidification, it was caked with mud. Initially, the team was planning to wash away the dirt to reveal a gray concrete structure, but they were so impressed by how it looked that they decided to leave it as it is. It was then that the architect sensed the atmosphere of a cave in the project and decided to redesign the building. Thus, the architectural design process was flipped, allowing the structure to determine the designs including the placement and number of glass pieces, as well as arrangement and size of the furniture.

House below ground level by Junya Ishigami

The plan is arranged with the restaurant on the north and the residence on the south. To go between the spaces, the visitor can walk through any one of the three courtyards that separate them. The chef invites guests to the restaurant as he would invite friends to his house. When the restaurant is closed, the hall serves as a place for the family to spend time together or for the children to study.

The Inside Home by Olgoo

Iranian architecture studio Olgoo has set a holiday home near the village of Ammameh, near Tehran, into its sloping site, in a bid to communicate a message about how new construction projects should consider the natural landscape rather than profit from it.

The Inside Home by Olgoo

The Inside Home project was designed in response to rapid development in the area, which has seen many of its green spaces replaced by construction, as the weak local law is unable to stand against the rapid conversion of gardens into small, saleable plots and the construction of dense buildings in them.

The Inside Home by Olgoo

Topped by a green roof, the residence merges with the surrounding landscape. As it is designed to be used by several families, the project comprises a pentagonal plan, that is split exposed concrete blocks with a courtyard sitting in the centre. The first of the three is intended for public living spaces, the second houses private bedrooms, while the third features utility spaces and a small swimming pool.

The Inside Home by Olgoo

While the communal spaces benefit from maximum light and view, the bedroom building on the contrary, has a minimum light to underscore a big difference between social and private life.

nCAVED house by Mold Architects (also header image)

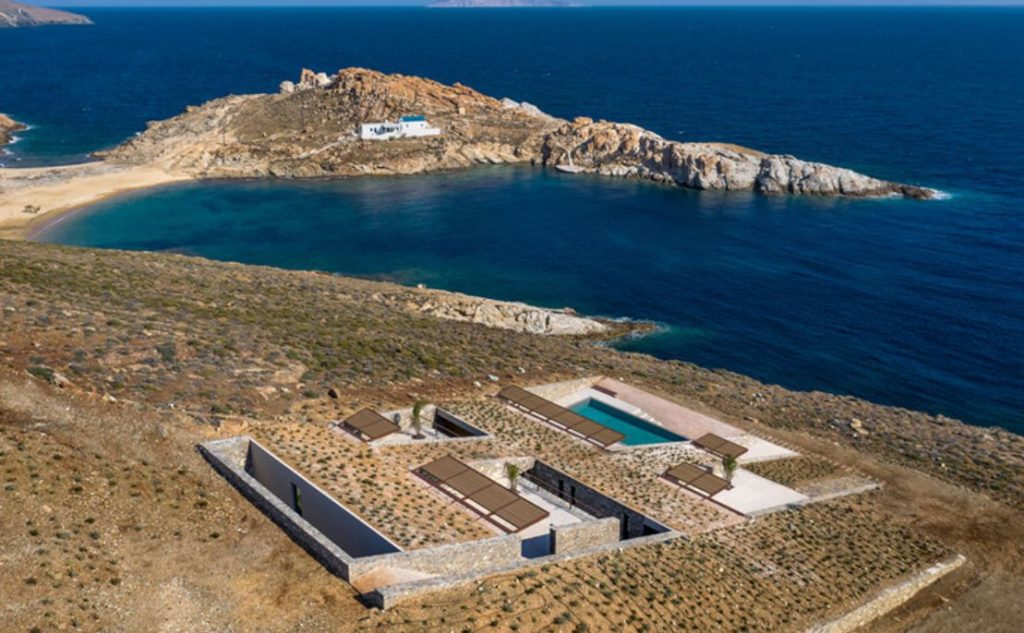

Inserted into the cliff side on the Greek island of Serifos, a house by Athens-based Mold Architects seems to hover just above the sea protected from the strong northern winds. Named nCAVED, the dwelling does not have an exterior form. Instead, it is comprised of a series of occupiable volumes subtracted from the earth, generating a three-dimensional ‘chess board’ of solids and voids.

nCAVED house by Mold Architects

The profile of the dwelling is defined by the heavy, retaining walls of dry stone, while contrasting perpendicular glass partitions are short and light and can be open along their entire length. This strict geometry is interrupted with the rotation of the outer axis of the rectangular grid, which opens up the living area offering a wider view for the occupants.

nCAVED house by Mold Architects

The in-caved areas, or ‘negative’ spaces, result from the severance and removal of the rocky earth. With the choice of materials and colour palette, the team managed to create a rough feeling of a natural cavity.