For decades, batteries have been a paradox of modern design. They enable mobility, connectivity, and intelligence, yet leave behind a trail of toxic waste and rigid form factors that constrain innovation. Today, a new wave of biodegradable batteries is challenging that status quo. By rethinking materials, manufacturing, and even what a battery fundamentally is, designers and scientists are creating energy systems that are safer, softer, and more aligned with natural life cycles.

At this year’s Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Singapore-based tech company Flint marked a major milestone by announcing that its rechargeable paper battery has officially entered production. This shift from lab-scale experimentation to manufactured cells signals more than technical readiness. It reflects a design philosophy that treats manufacturability as a core feature, not an afterthought. As founder and CEO Carlo Charles put it, reinventing batteries is as much about building something that can be made reliably as it is about chemistry.

Flint’s Paper Battery

Flint’s battery stands apart by removing lithium, cobalt, and nickel entirely from the equation. Instead, it relies on zinc and manganese electrodes paired with a water-based, non-flammable electrolyte and a cellulose separator. The result is a thin, flexible battery sealed in a pouch that can bend, be punctured, or even exposed to flame without leaking or exploding. This robustness opens new doors for industrial designers who have long been constrained by rigid, volatile battery packs.

Flint’s Paper Batter

End of life is where Flint’s design truly breaks from convention. Once depleted, components of the battery can be recycled or simply buried in soil, where they decompose within six weeks without leaving harmful residues. By avoiding lithium mining, which has been linked to severe environmental and social impacts in regions like Chile’s Atacama Desert, the battery also addresses upstream sustainability concerns. Flint claims the technology is nearly half the cost per kilowatt-hour compared to lithium alternatives, reframing sustainability as both an ethical and economic advantage.

With pilot customers including Logitech and Amazon, Flint’s paper battery is already eyeing real-world applications such as e-readers and streaming devices. Looking ahead, the company envisions uses ranging from medical technology to electric vehicles and even space systems. Its flexible form factor hints at products that no longer need to be designed around a battery, but instead integrate energy storage seamlessly into their structure.

Empa’s Fungal Power Cells (also header image)

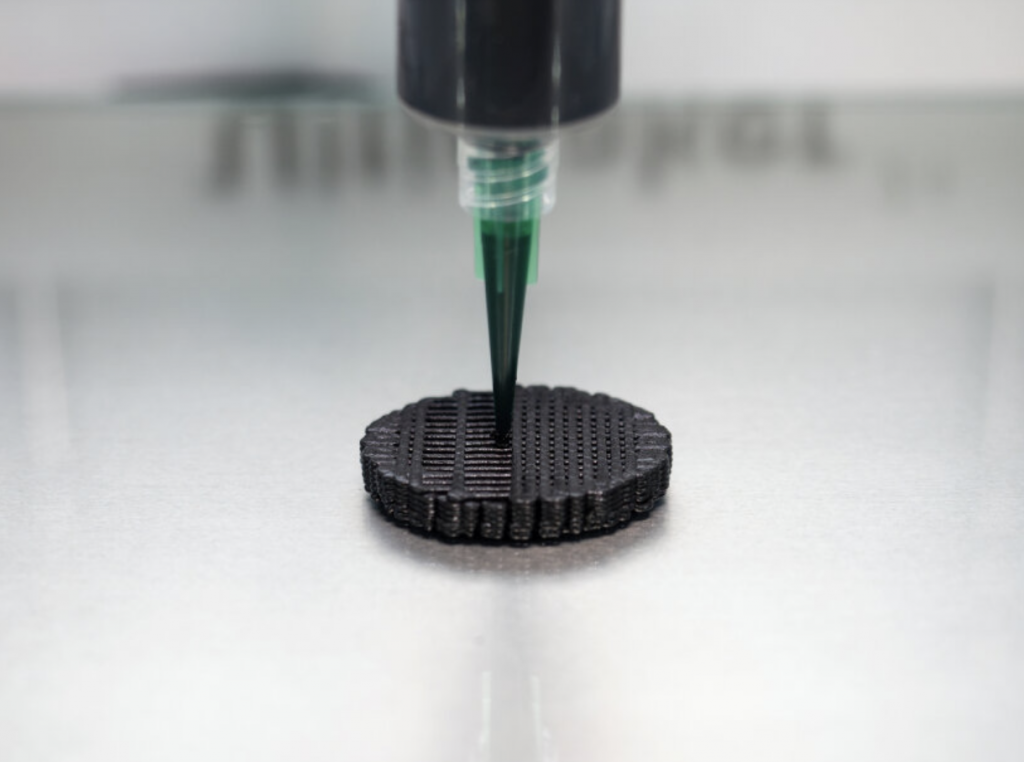

If Flint’s work reimagines batteries as manufactured objects, researchers at Empa in Switzerland take an even more radical approach. Their 3D printed biodegradable “battery” is alive. Developed in the Cellulose and Wood Materials laboratory, this device combines two types of fungi into a microbial fuel cell that converts sugar into electricity. After powering small devices for several days, it quite literally digests itself from the inside.

Empa’s Fungal Power Cells

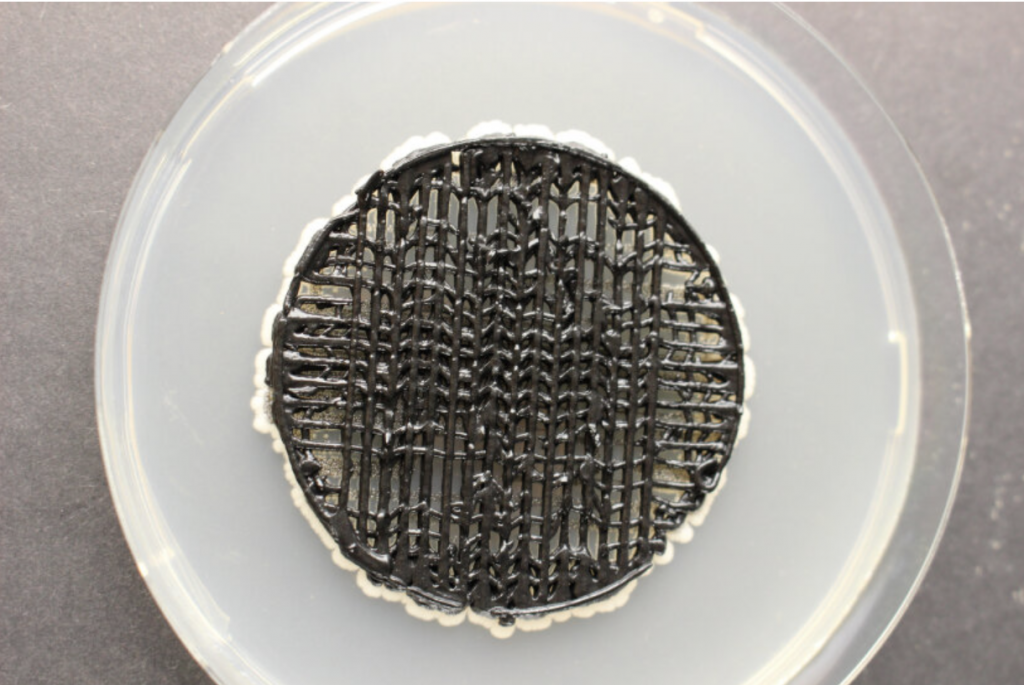

Strictly speaking, the researchers are careful to note that this is not a battery in the traditional sense. It is a microbial fuel cell, where a yeast fungus at the anode releases electrons through its metabolism, while a white rot fungus at the cathode produces enzymes that capture and conduct those electrons. Both organisms are embedded directly into a cellulose-based printing ink, allowing the entire system to be fabricated through 3D printing without harming the living cells.

Empa’s Fungal Power Cells

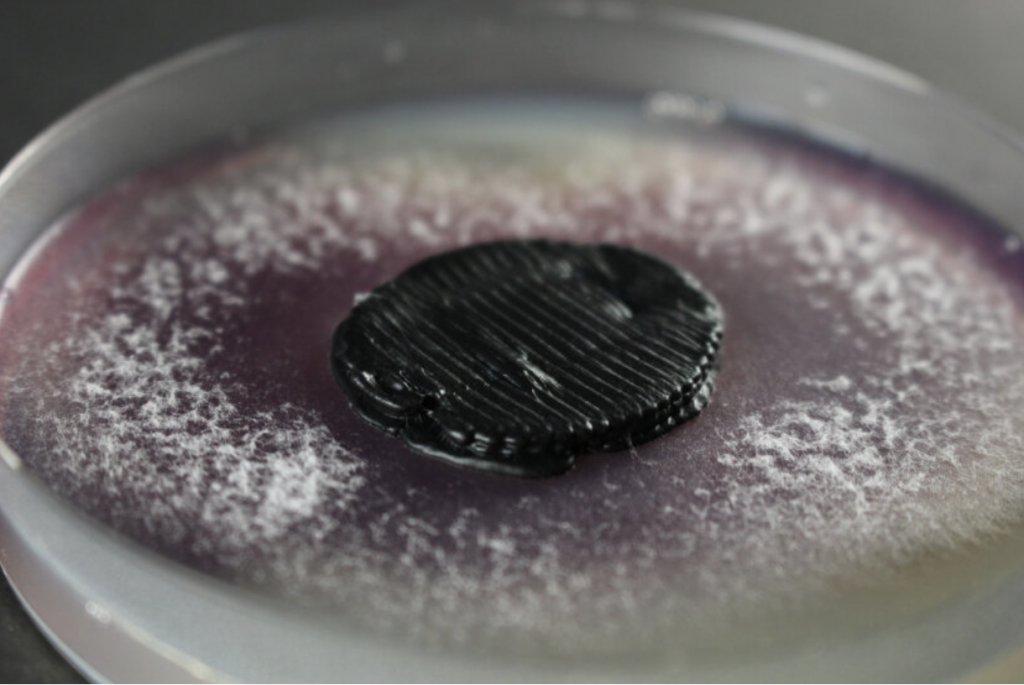

The design implications are striking. The printed structure is electrically conductive enough to power small sensors, particularly for agricultural monitoring or environmental research, and it is entirely non-toxic. Cellulose sourced from wood or cotton forms the structural base, and the fungi can even consume this material as a nutrient once the device is no longer needed. Users can store the battery in a dried state or encase it in beeswax, then activate it simply by adding water and sugar.

Empa’s Fungal Power Cells

While its energy output is modest, the fungal battery reframes the role of power sources in design. Instead of maximizing longevity and capacity at all costs, it prioritizes temporary usefulness, safety, and graceful disappearance. In doing so, it suggests a future where certain devices are designed to exist only as long as they are needed, then return harmlessly to the ecosystem.

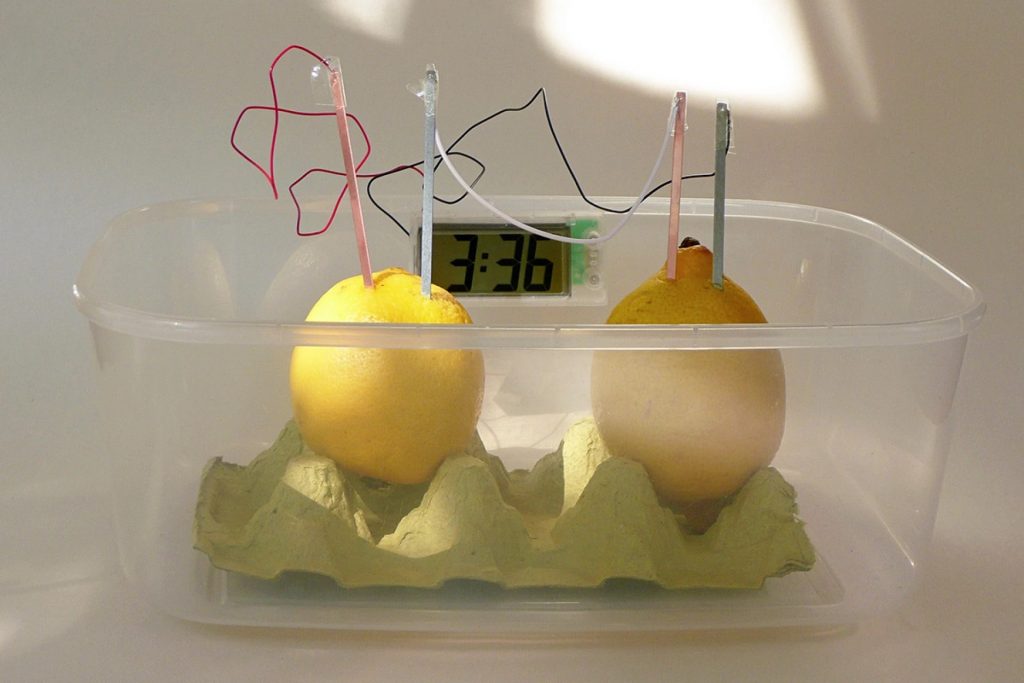

McGill University’s Gelatin Battery

A similar ethos underpins research from McGill University in Canada, where scientists have developed a biodegradable battery inspired by childhood science experiments. Motivated by the environmental damage caused by discarded batteries, the team explored how citric acid, familiar from lemon batteries, could improve a gelatin-based electrolyte. The result is a power source made from relatively benign materials that can safely degrade in soil.

McGill University’s Gelatin Battery

The battery uses gelatin as its electrolyte, with magnesium and molybdenum as electrodes. On their own, these materials face limitations, particularly the tendency of magnesium to form a layer that halts the electrochemical reaction. By adding citric acid, and later lactic acid, the researchers found they could break down this layer, extending both the battery’s lifetime and its voltage. The approach blends playful inspiration with serious materials science.

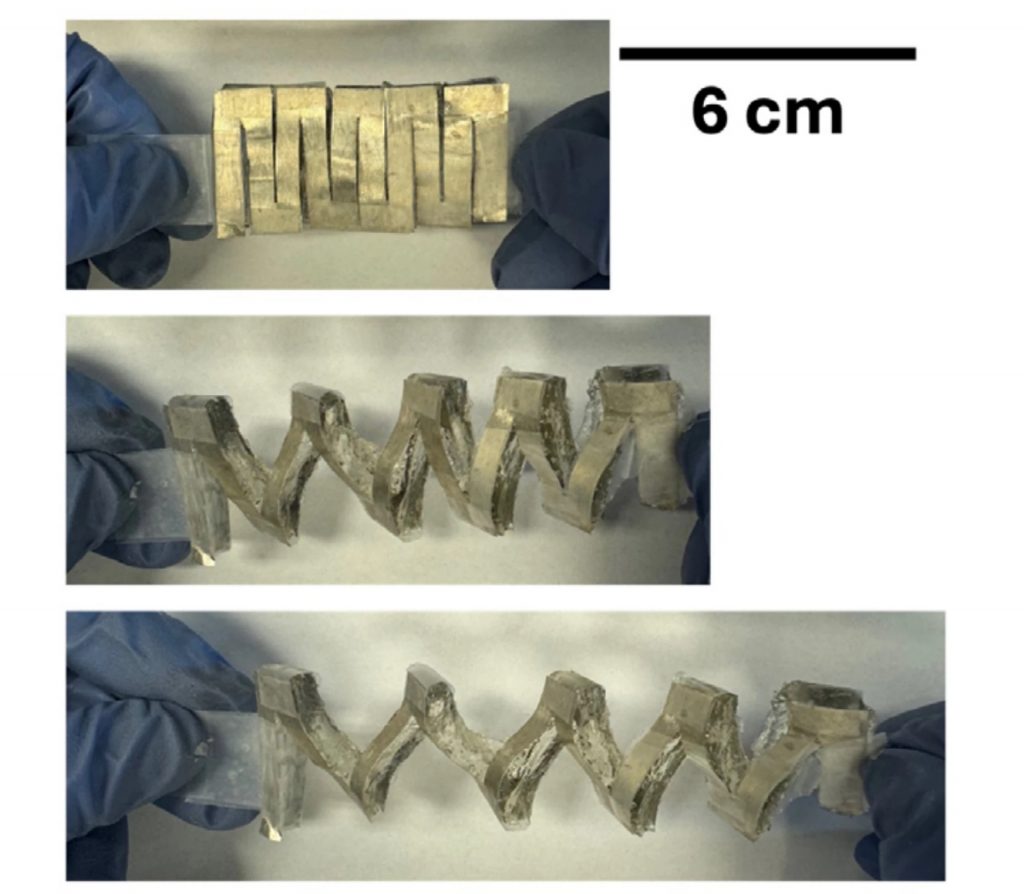

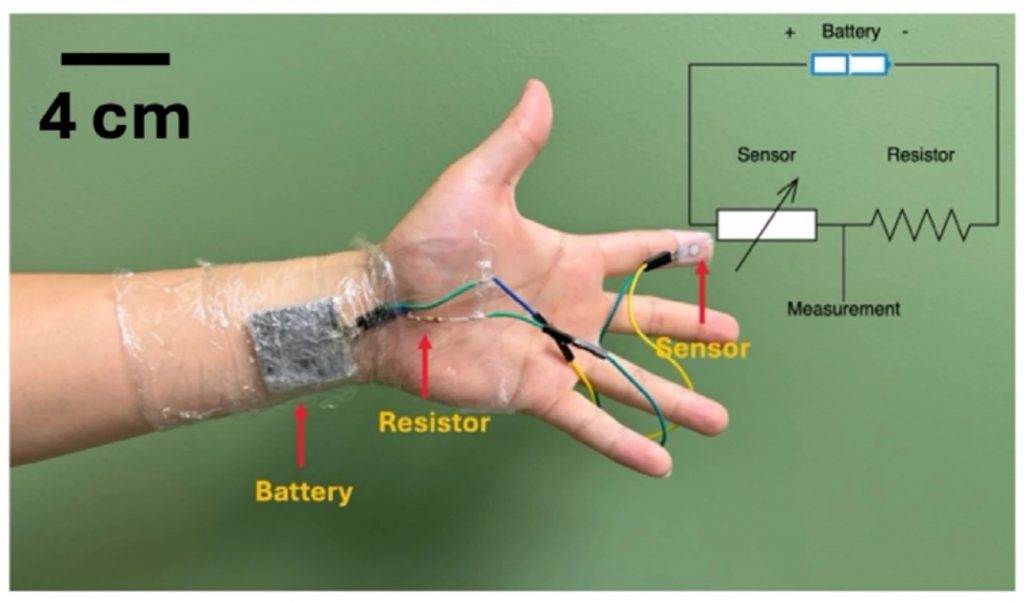

What elevates this development from clever chemistry to design innovation is its mechanical flexibility. Drawing on kirigami, the Japanese art of cutting paper into stretchable forms, the team patterned the battery so it could stretch up to 80 percent beyond its original length while maintaining stable voltage. This made it suitable for wearables and medical devices, where rigid components are often a poor fit.

McGill University’s Gelatin Battery

In testing, a battery barely one square centimeter in size successfully powered a wearable finger pressure sensor, delivering performance comparable to a standard AA battery for that application. When depleted and immersed in a saline solution, most components degraded within two months. This balance of functionality, flexibility, and controlled decomposition highlights how biodegradable batteries can meet real design requirements without leaving a lasting environmental footprint.