Traditional bricks are heated at temperatures of more than 1,000 degree Celsius, producing huge carbon dioxide emissions. The race is on to create more sustainable building materials for the construction industry. Because of the increasing integration of the design, science and engineering domains, designers and researchers work to define the compositions of materials or even create materials for desired functions, such as pollution control, climate responsiveness, sound absorption, thermal barriers, shape and colour changing, and biodegradability. Among recent innovations are eco-friendly bricks made of loofah, no-heat bricks made from urine, and structures grown from mushroom mycelium.

Inspired by the biophilic design, which focuses on providing a strong connection between humans and nature, a group of researchers at the Indian School of Design and Innovation in Mumbai led by Shreyas More and Meenal Sutaria has developed eco-friendly bricks. Named Green Charcoal, they are made of soil, cement, charcoal and organic loofah, the plant commonly used for bath sponges.

Green Charcoal bio-bricks by Indian School of Design and Innovation Mumbai (alos header image)

Lightweight and biodegradable, the bricks don’t need to be reinforced as the luffa provides all the necessary structural support and flexibility. Due to the natural gaps in the loofah’s fibrous network, the new material is up to 20 times more porous than conventional concrete bricks. This enables increased biodiversity in cities as well as helps provide healthy urban solutions for people.

Green Charcoal bio-bricks by Indian School of Design and Innovation Mumbai

On the one hand, the numerous air pockets enables the bio-bricks to harbour animal and plant life. Simultaneously, the act as thousands of tiny water tanks to reduce the blocks’ temperature, cooling interior environments. Charcoal that is used in small amount on the brick’s surface serves to purify the air by absorbing nitrates. The team believes that when used in the facades, compound walls and dividers that follow the road network, the Green Charcoal bricks will help clean the air and control rise in temperature, while inspiring more positive and happier societies.

Green Charcoal bio-bricks by Indian School of Design and Innovation Mumbai

Although the bio-bricks need far less aggregate than standard concrete, they still require cement, one of the world’s largest sources of carbon dioxide emissions, although it is a slightly reduced amount. Currently, the team behind the project is exploring different surface treatments to create a variety of bricks.

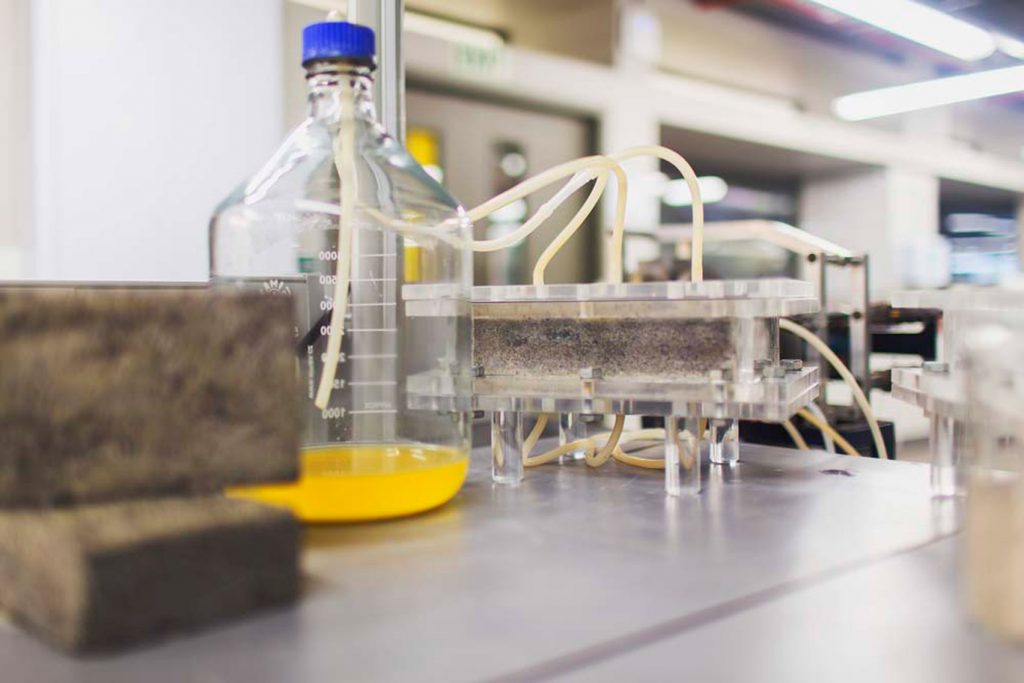

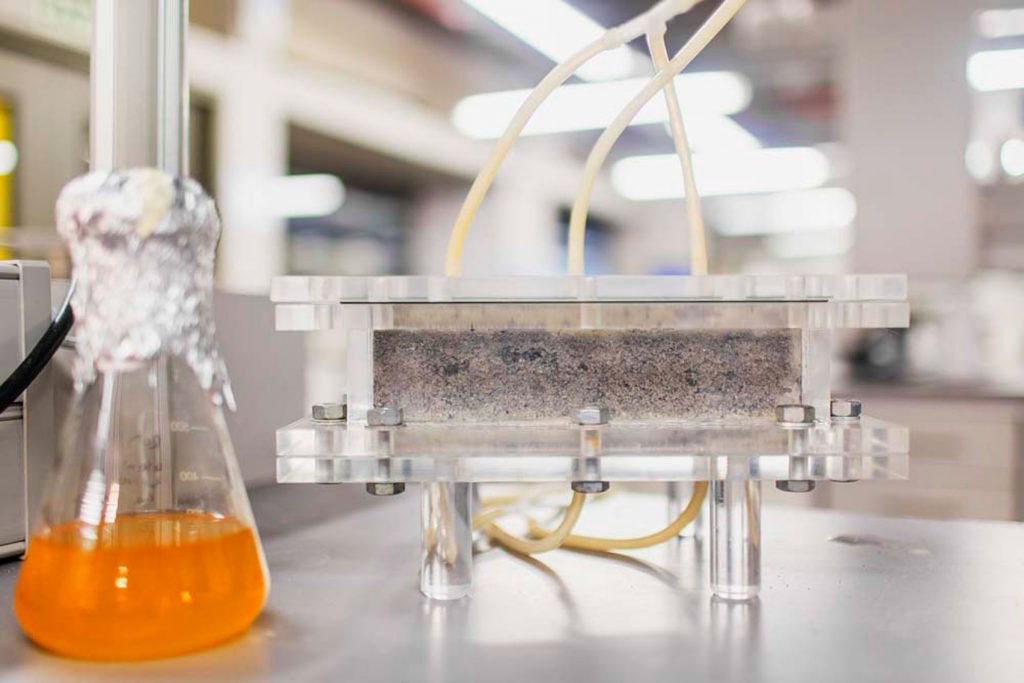

Bio-bricks from human urine by Suzanne Lambert of UCT

Bricks by University of Cape Town masters student Suzanne Lambert are made using recovered human urine and living bacteria that produces the enzyme urease. The process utilized, which is called microbial carbonate precipitation, enables fabricating bricks of different sizes, shapes and strengths. Lambert’s supervisor at the UCT, Dyllon Randall, likens it to the way seashells are formed.

Bio-bricks from human urine by Suzanne Lambert of UCT

Human urine, collected using a special fertiliser-producing urinal, loose sand and the living bacteria are combined in a brick-shaped mould. The urease produced by the bacteria triggers a chemical reaction, breaking down the urea in urine, while producing calcium carbonate, the main component of cement. This solidifies the bricks at room temperature, which helps lower their carbon footprint, and the longer they are left in their moulds, the stronger they get.

Bio-bricks from human urine by Suzanne Lambert of UCT

In contrast to previous efforts, Lambert’s product is the first of its kind to be brick shaped, and also the first to use human urine instead of a synthetic compound. The team sees much potential for the process’s application in the real world.

Mushroom bricks by Phil Ross

Patented “mushroom bricks” by San Francisco based designer and artist Phil Ross are also grown rather than manufactured. He grows mycelium, the fibrous roots that make up the vast majority of fungus lifeforms, in bags of sawdust, before drying them out and cutting them with extremely heavy-duty steel blades. This becomes possible because mushrooms digest cellulose in the sawdust, converting it into chitin, the same fiber that insect exoskeletons are made from.

Mushroom bricks by Phil Ross

Once they dry, the resulting bricks are incredibly durable, lightweight, waterproof, non-toxic, fire-resistant, and biodegradable. They have the feel of a composite material with a core of spongy cross grained pulp that becomes progressively denser towards its outer skin. The surface is incredibly hard, shatter resistant, and can handle enormous amounts of compression. A variety of different lacquers and finishes can also be applied to the outer layer of the bricks to seal them and give them a glossy finish.

Mushroom bricks by Phil Ross

To demonstrate the potential of the material, Ross has built a showpiece called “Mycotecture”—a 6×6 mushroom brick arch from fungus Ganoderma lucidum, or Reishi mushrooms.