There is hardly a warmer image than that of a lighthouse emitting welcoming glow amidst the darkness of the night. Architects employ translucency of glass facades to turn buildings into large-scale lanterns that draw one closer with an inviting sense of openness, just like a moth is attracted to a light.

H1002 residential building by 314 architecture studio (also the header image)

314 architecture studio based in Glyfada, Greece, has designed a futuristic residential project in the heart of Athens. The architects utilize frosted glass panels as a prominent feature of the building to explore the idea of creating spaces using physical transparency.

H1002 residential building by 314 architecture studio

Named H1002, the building is composed of five different properties, one of which is connected to the neoclassical building dating back to 1870s. Each property is a blurred transparent cell, which creates a warm lantern-like effect on the outside. The frosted glass works as a part of interior as well too, used on each wall it opens up closed spaces to both light and air.

H1002 residential building by 314 architecture studio

Hidden lights are placed behind the glass panels offering the feeling of natural light penetrating the residence. The transparency visually increase the size of the spaces, and at the same time allows flexibility in the organization of the floorplan and produces ambiguous spatial perception: areas appear to be separated, yet combined.

Lasvit headquarters by OV-A

Prague-based architectural studio OV-A has completed the new headquarters of glassmaking company Lasvit, which includes also a sleek black cement house and a striking glass house. Conceived as a part of the project seeking to restore some of the town’s historic buildings and regenerate the region’s glassblowing traditions, the new building shows how traditional materials can be united with modern design and cutting-edge technology.

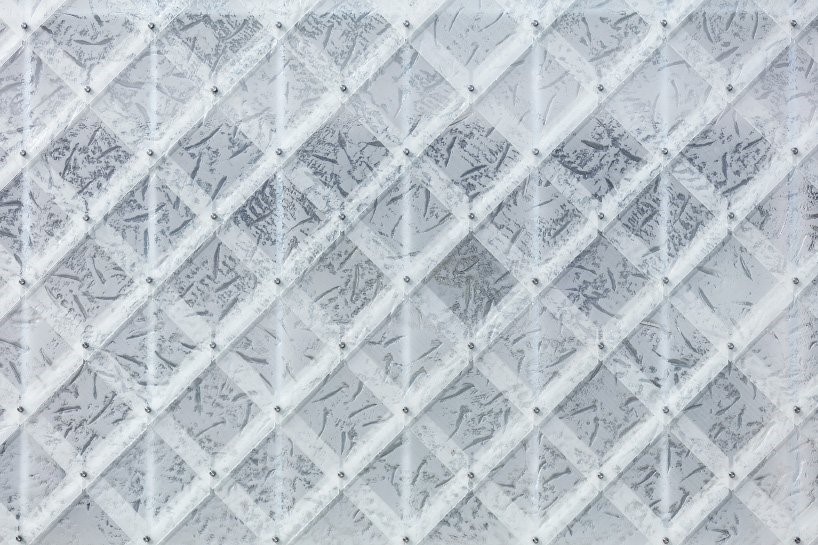

Lasvit headquarters by OV-A

Designed as a lighthouse, the façade is clad with glass tiles inspired by traditional slate shingles used for the region’s roofs — square templates are placed diagonally, one on top of the other. The tiles have a texture, which is similar to that of slate, and were developed specifically for the project by Lasvit. The adjacent black house is covered with a cement wall tile.

Lasvit headquarters by OV-A

The building also includes a hall where intricate and large scale kinetic glass installations Lasvit is known for can be displayed under different lighting conditions.

Nová Ruda kindergarten by Petr Stolín Architekt (via dezeen)

Designed by the local architecture studio Petr Stolin Architekt , the Nova Ruda kindergarten in the town of Liberec, Czech Republic features a translucent façade of fiberglass – the solution which allows to balance outdoor space with the need for privacy.

Nová Ruda kindergarten by Petr Stolín Architekt (via dezeen)

The central building is wrapped in two layers of trapezoidal fiberglass, the gap between them forming a long courtyard hidden from the street. The first layer is a wooden frame covering the walls of the inner building, while afterwards the whole structure is wrapped in a kind of a steel and fiberglass shell.

Nová Ruda kindergarten by Petr Stolín Architekt (via dezeen)

The inner terrace space includes two walking paths and staircases for those inside to move from a more private garden to the more exposed perimeter walkway. The playroom situated on the first floor takes advantage of the connection to the courtyard.

Nová Ruda kindergarten by Petr Stolín Architekt (via dezeen)

The views outside are possible through large openings aligned in both layers, while in the nighttime the cut-outs in the fibreglass shell glow behind the outer skin. Terraces and viewing areas on the rooftop are strategically placed alongside the openings, looking back down into the central courtyard.

Institute for Contemporary Art for the VCU by Steven Holl Architects

New York-based Steven Holl Architects designed the new Institute for Contemporary Art for the Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia. The building forming a gateway to the University comprises a series of irregularly shaped blocks that slot together. Although externally the building feels like separate volumes, spaces merge together inside.

Institute for Contemporary Art for the VCU by Steven Holl Architects

The façade is covered in matte translucent glass skin offering a blurry view in and pre-weathered titanium zinc panels. The two material share the same greyish tone, which gives the building an ambiguous shifting presence, as it transforms from monolithic opaque to multifarious translucent, depending on the light.

Institute for Contemporary Art for the VCU by Steven Holl Architects

Encompassing four galleries, each with a different character, the ICA aims to become an instrument for exhibitions, film screenings, public lectures, performances, symposia, and community events, engaging the University, the city, and beyond.

Institute for Contemporary Art for the VCU by Steven Holl Architects

The building is also designed to be as sustainable as possible. It is heated and cooled with geothermal wells, designed to retain heat in winter and provide cooling in summer. Window and skylights are placed strategically to ensure spaces receive plenty of natural light, reducing the need for artificial lighting.