Facades of perforated metal can be as eye-catching as they are practical. As advanced computer based manufacturing methods allow creating stunning patterns on metal sheets, the perforated screens are no longer utilized solely as a way to provide ventilation and shielding from glare.

Profiles office building by Belzberg Architects (also header image)

Situated in a mid-block property in Mexico City, Profiles by California-based Belzberg Architects is a commercial office space with a dynamic façade that increases visibility of the building from a variety of perspectives and creates a memorable experience for occupants and passersby. The design was developed as a response to the building traditions throughout the city, with the vast majority of existing buildings only considering the street-facing façade, while leaving their side facades blank and exposed.

Profiles office building by Belzberg Architects

Constructed next to a three-story neighbor, the structure transforms the mid-block property into a south-facing corner lot. This setback not only activates the side façade but also enables greater access to fresh air and daylight.

Profiles office building by Belzberg Architects

In this project, perforated steel skin aims to enhance the connection between the exposed facades. The featured variable apertures are optimized for ventilation and light, and maintain privacy and visibility for occupants. The flaps attached to select punctures create an additional pattern of curved vertical lines that mimics a curtain being gathered to reveal beyond.

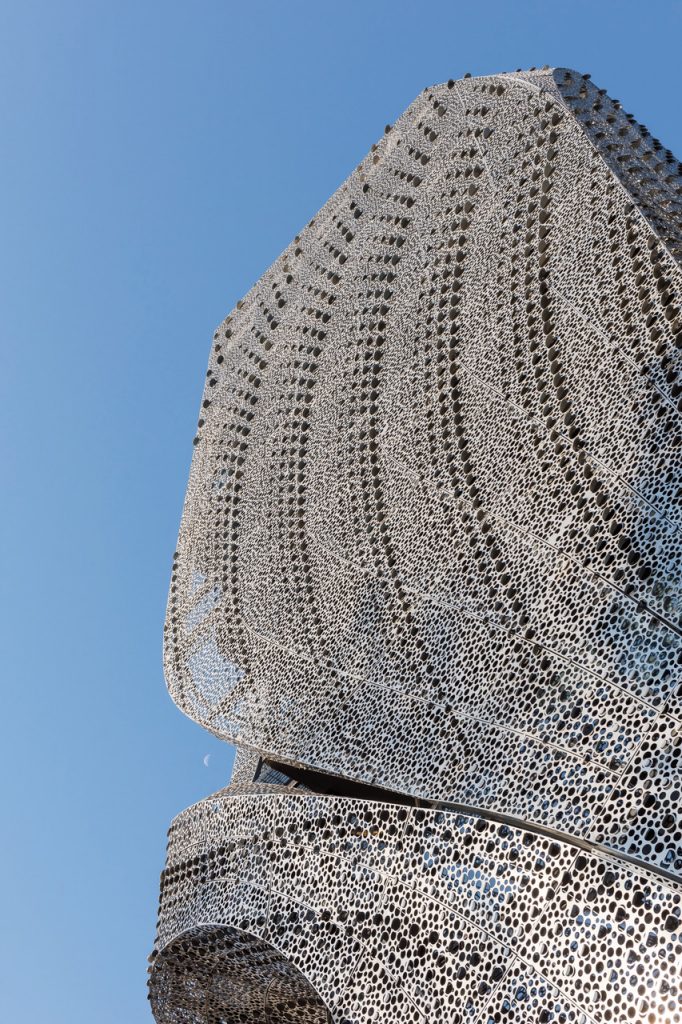

Kalvebod Fælled School by Lundgaard & Tranberg Architects (via)

Similarly, perforated metal panels define the exterior of a Kalvebod Fælled school building in Denmark designed by local by Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter. The design of the round building features rings of classrooms arranged around a centrally-located triple-height gym.

Kalvebod Fælled School by Lundgaard & Tranberg Architects (via)

Designed to shield the a large number of small windows placed in staggered arrangements inside the classrooms from direct sunlight, the metal screens can move automatically in response to illumination levels or be moved manually. Externally, the perforated panels are organized in vertical lines along the façade. Alternating with solid ones, they create a characteristic geometric pattern.

Kalvebod Fælled School by Lundgaard & Tranberg Architects (via)

The floorplan of the building is equally remarkable. As the school is used by children during the day, and doubles as a community in the evening for night-classes, sports and performances, the architects designed the a series of open and flexible spaces that can facilitate all these uses. The round central space is occupied by a gym in the first to third floors, with a ground-floor auditorium underneath it and a roof terrace on the top.

Kalvebod Fælled School by Lundgaard & Tranberg Architects (via)

Surrounding the auditorium at ground floor level is a large atrium that hosts events such as festivals or markets. On upper levels, a ring-shaped circulation route provides access to the classrooms, sitting around the perimeter. These double as a balcony to view the gymnasium and atrium below, growing in width at points on either side to create larger seating areas.

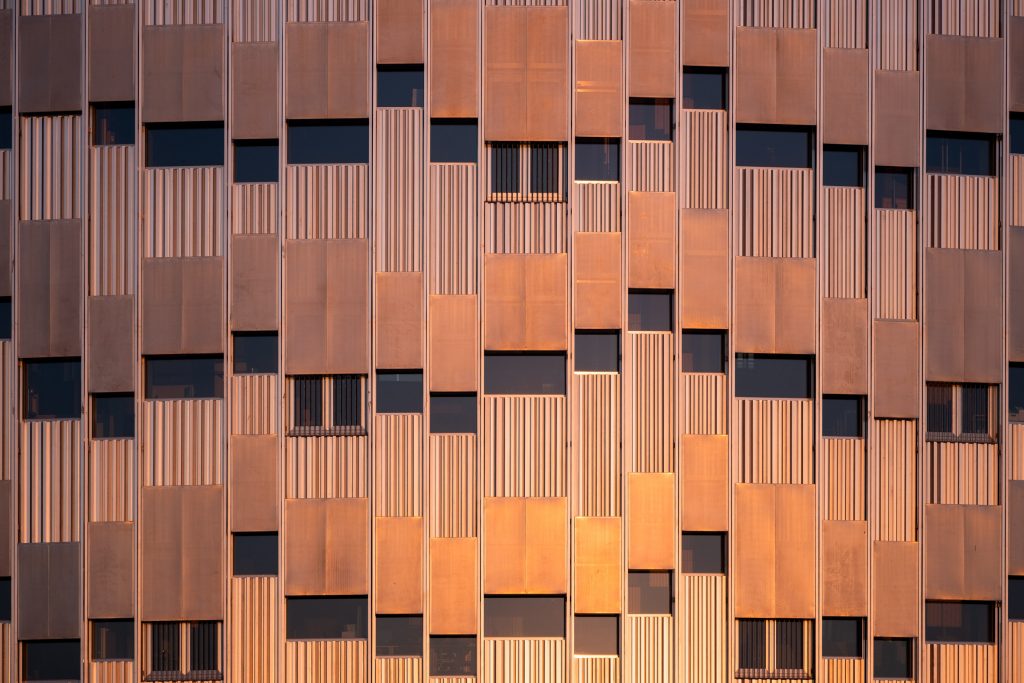

London’s Bunhill 2 Energy Centre by Cullinan Studio

Local practice Cullinan Studio was commissioned by Islington Council to develop a pavilion to house London’s Bunhill 2 Energy Centre, a revolutionary project that uses waste heat from nearby London Underground tunnels to warm over 1,000 homes, leisure centres and a local school. Being the first of this kind in the world, Bunhill 2 Energy Centre provides a blueprint for decarbonising heat in potential future schemes improving air quality and making cities more self-sufficient in energy.

London’s Bunhill 2 Energy Centre by Cullinan Studio

The architects were asked to create the architecture that would celebrate this new typology of heat networks – just as Joseph Bazalgette had revolutionised the design of the public water systems in the 19th century and Sir Giles Gilbert defined the appearance of the phone box in the 20th century.

London’s Bunhill 2 Energy Centre by Cullinan Studio

The pattern on the perforated metal panels serve to minimize the visual impact of the new building on the local community. Its block-shaped motifs echo the layout of flats within the adjacent King Square Estate, which the heat network now serves. The deep red colour pays homage to the hue of the tiles found on London Underground station, as well as the copper pots of gin distilleries that used to be located near the site.

London’s Bunhill 2 Energy Centre by Cullinan Studio

The perforated pattern ebbs and flows in response to the varying degrees of ventilation required for the equipment behind. Simultaneously, the cladding forms part of a prefabricated structure designed to be easily removed to maintain machinery.